Researchers at Stanford University (USA) have stated that the property dye which has not yet been tested on humans, may eventually be used to detect injuries or tumors.

To make this discovery, scientists looked into brain and the bodies of living animals, and eventually discovered that the common food dye tartrazine can temporarily make the skin, muscles, and connective tissues transparent.

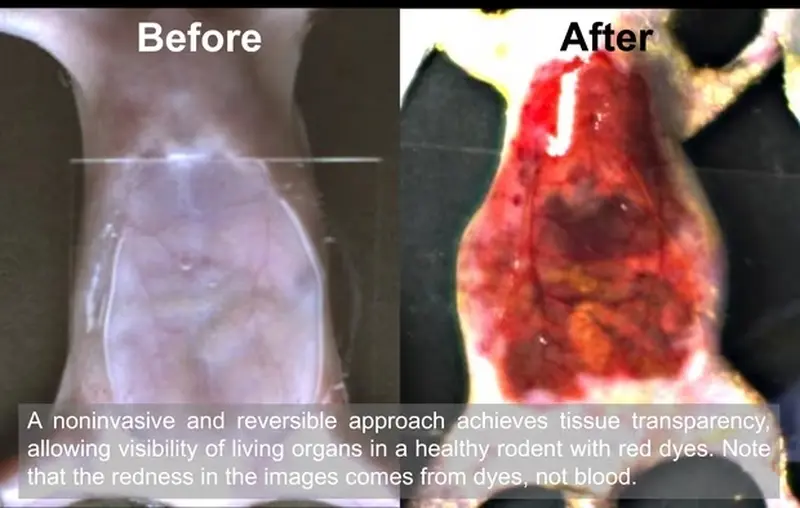

Applying dye to the mouse’s abdomen made its liver, intestines, and bladder clearly visible through the skin. Additionally, applying dye to the rodent’s scalp helped scientists see the blood vessels in its brain, the publication reported. The Guardian .

According to researchers, processed skin It restored its normal color as soon as the dye was washed off. Scientists believe that this procedure opens up numerous possibilities for its application in humans, such as detecting injuries, locating veins for blood draws, monitoring digestive disorders, and identifying tumors.

“Instead of relying on invasive biopsies, doctors could diagnose deeply located tumors simply by examining human tissues without the need for invasive surgical intervention,” said Dr. Gohsong Gong, a senior researcher on the project. He believes that this method could potentially make blood draws less painful, as phlebotomists would find it easier to locate veins beneath the skin.

What is the secret of the dye’s strange property?

This discovery resonates with the story of Griffin from H.G. Wells’ novel “The Invisible Man” (1897). In the plot, a brilliant yet doomed scientist discovers that the secret of invisibility lies in matching the refractive index of an object, or its ability to bend light, with the refractive index of the surrounding air.

When light penetrates biological tissue, most of it is scattered because the structures inside, such as fat membranes and cell nuclei, have different refractive indices. When light transitions from one refractive index to another, it bends, making the tissue opaque. The same effect causes a pencil to appear bent when placed in a glass of water.

Dr. Zhihao Ou and his colleagues at Stanford suggested that it defies common sense that certain dyes can facilitate the passage of light waves of specific wavelengths through the skin and other tissues. Dyes that have a strong absorption capacity alter the refractive index of the tissues that absorb them. This helps scientists compare the refractive indices of different tissues and suppress any scattering.

How did the experiments go?

In a series of experiments, researchers demonstrated how fresh chicken breast became transparent to red light within minutes of being immersed in a tartrazine solution. This yellow food dye is used in some chips, beverages, and other products. The dye reduced light scattering within the tissue, allowing the rays to penetrate deeper.

Then the team applied the yellow dye to the lower abdomen of the mouse, making the intestines and internal organs visible through the transparent skin. In the second experiment, the scientists applied the dye to the shaved head of the mouse and used laser speckle contrast imaging to observe the blood vessels in the rodent’s brain.

“The most surprising thing about this study is that we usually expect dye molecules to make things less transparent. For example, if you mix blue ink from a pen with water, the more ink you add, the less light can pass through the water. In our experiment, when we dissolve tartrazine in an opaque material (such as muscle or skin, which typically scatter light), the more tartrazine we add, the more transparent the material becomes. But only in the red part of the light spectrum. This contradicts what we usually expect from dyes,” noted Mr. Gong.

Interestingly, after the paint is washed off, the skin returns to its natural color. Currently, the transparency is limited by the depth of the dye’s penetration, but scientists have suggested that with microneedle patches or dye injections, the dye could act deeper.

The procedure has not yet been tested on humans. First and foremost, researchers need to prove its safety, especially if the dye is to be injected under the skin.

In the accompanying article, experts Christopher Rowlands and John Goretsky from Imperial College London suggested that this procedure would generate “extraordinarily wide interest,” as it, combined with modern imaging techniques, would help scientists more easily detect tumors beneath tissues. “Herbert Wells, who studied biology under Thomas Huxley as a student, would undoubtedly approve of this,” they wrote.

The results of the study were published in the journal Science.