This fascinating biography tells the story of how a “struggling elementary school student,” who lost his mother at the age of eight, compensated for his lack of knowledge at two British universities and became a prominent scientist, challenging established beliefs about human origins with his “heretical” conclusions. What led this hereditary English naturalist and explorer, who was among the first to argue that all living organisms evolve over time from common ancestors, to clash with the church? What was groundbreaking about his scientific views, and what contributed to these revolutionary discoveries?

What Charles Darwin Accomplished

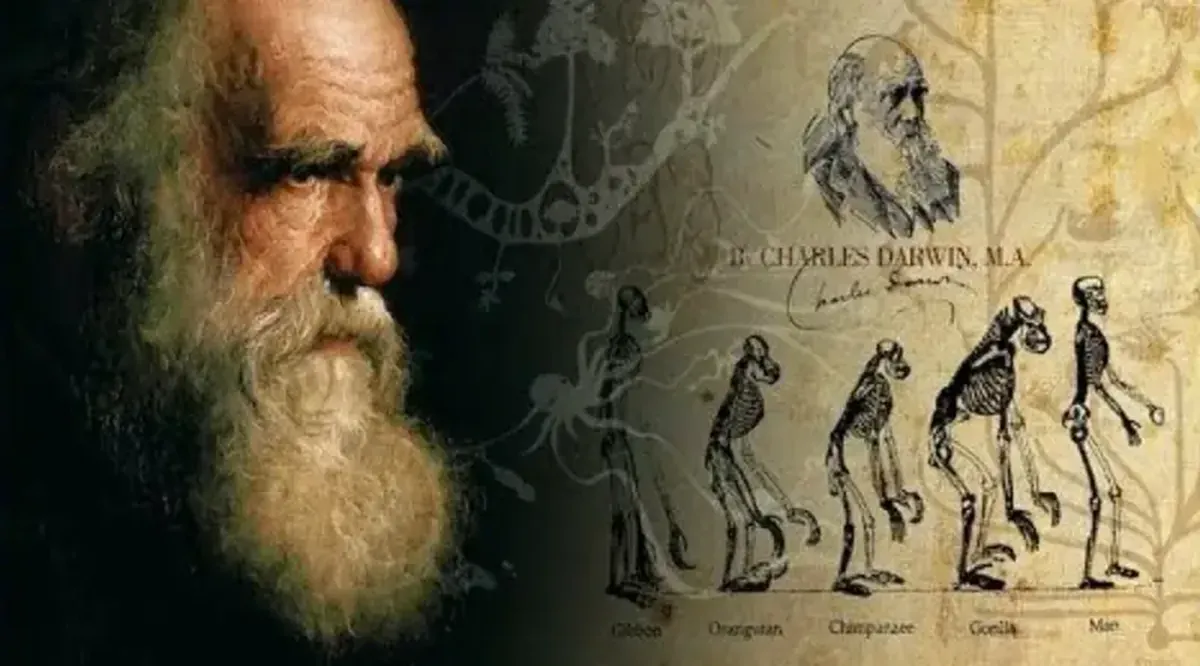

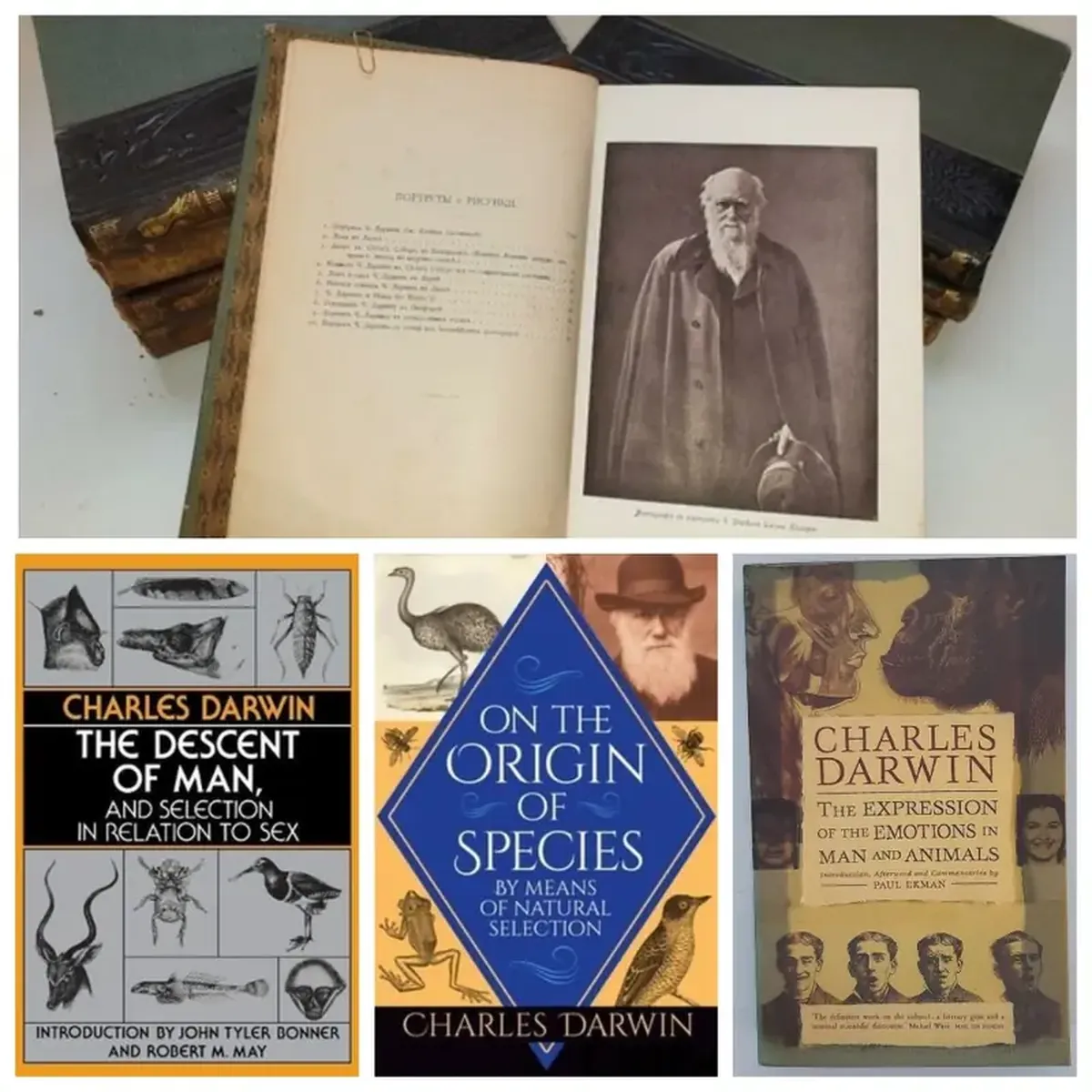

Knowing the stories of his predecessors, naturalists Carl Linnaeus and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (the former was excommunicated for placing humans among primates, while the latter died in obscurity developing his theory of evolution), Darwin hesitated for 20 years to publish his theory of evolution out of fear of backlash. While theologians denied evolution, insisting that everything was created by God, this innovator dared to disagree. A proponent of the idea that all species of living organisms evolved from common ancestors, he identified natural selection as the primary mechanism of evolution in 1859 (later, he elaborated on the theory of sexual selection).

Charles Darwin authored one of the first comprehensive studies on human origins. He asserted the existence of a common ancestor for both apes and humans. He also published one of the early works in ethology, studying emotional expressions in humans and animals, created a model for the formation of coral reefs, became the world’s leading expert on barnacles, and experimentally determined the laws of heredity. Darwin’s ideas and discoveries form the foundation of modern synthetic theory of evolution and are fundamental to biological science in explaining biodiversity. The term “Darwinism” describes the theory that defines contemporary scientific views on evolution as a whole.

Hereditary Naturalist

On February 12, 1809, the fifth of six children was born to wealthy physician and financier Robert Darwin and his wife, Susannah, at their family estate, Mount House in Shrewsbury. On his father’s side, the boy’s grandfather was the naturalist Erasmus Darwin, and on his mother’s side, the artist Josiah Wedgwood. A man of broad views, his father allowed his son to take communion in the Anglican Church (the state church of England adheres to the doctrines of Scripture but allows for individual interpretation), while his parents and paternal brothers were Unitarians—a liberal religion that promotes a “free and responsible search for truth” in spiritual development.

By the time he entered elementary school, Charles had already engaged in natural experiments and collecting. In 1817, at the age of eight, Darwin lost his mother, and his upbringing fell entirely on his widowed father. Along with his older brother Erasmus, Charles attended Shrewsbury School, where the passionate nature enthusiast found himself studying classical languages that bored his curious mind. The teachers failed to spark even the slightest interest in the “struggling student”: lessons in literature held less significance for the young naturalist than exploring butterflies and beetles. Within a year, he had gathered his first collections of insects, shells, and minerals, and later developed an interest in chemistry.

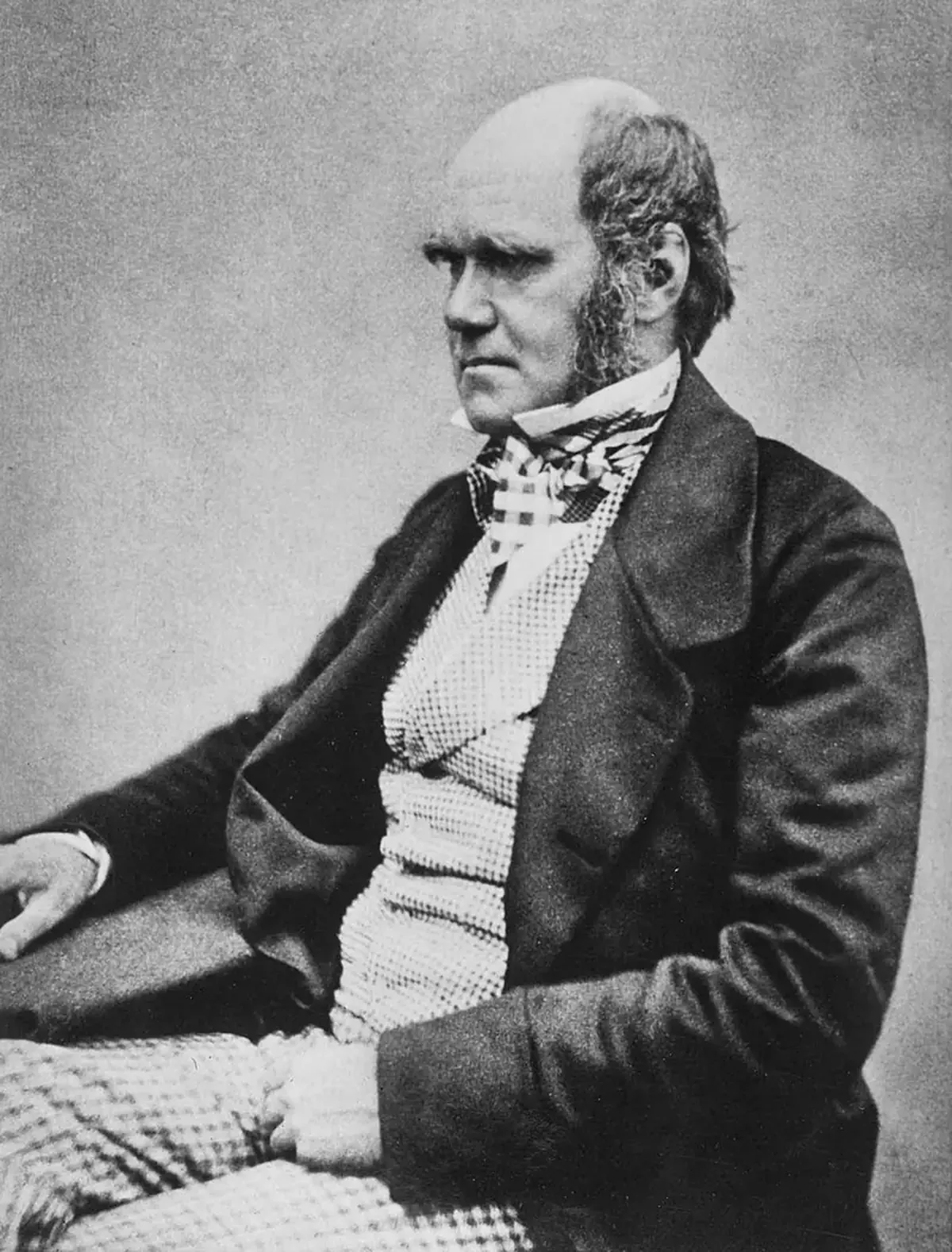

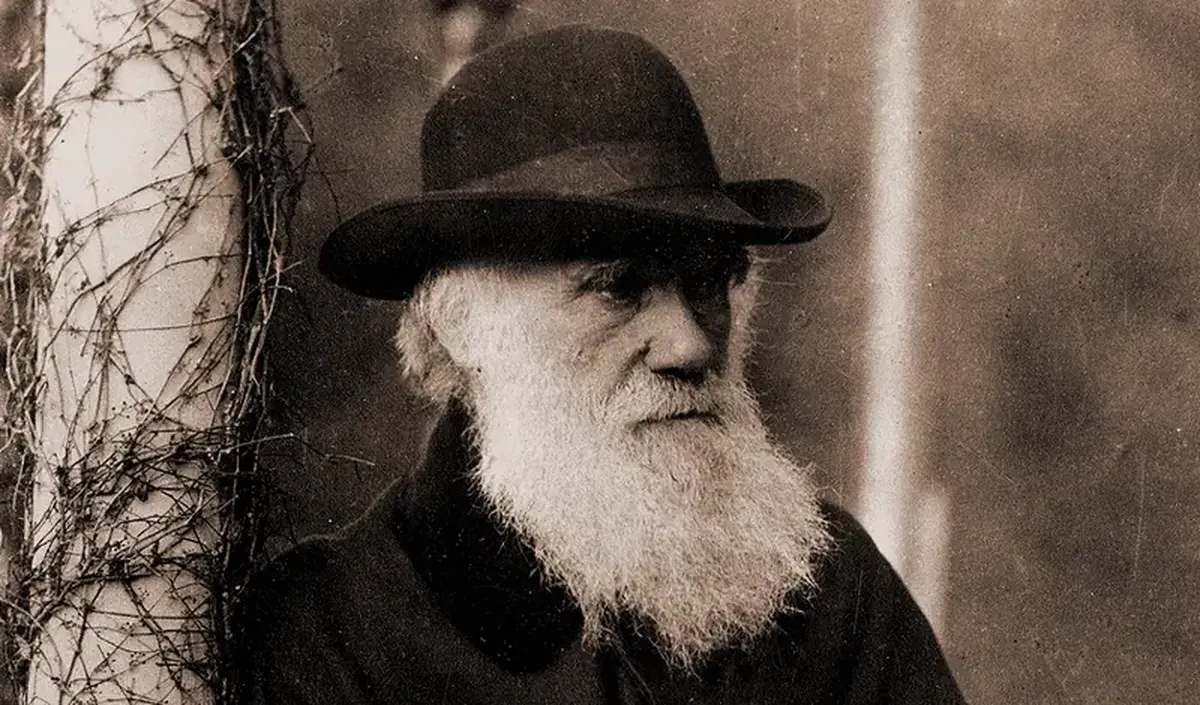

Charles as a child (1816)

His Universities

With a mediocre school certificate, Charles set off with his brother Erasmus to continue his education at the University of Edinburgh, trying his hand at medical practice before following in his father’s footsteps: in the summer of 1825, the young man assisted his father in providing aid to the poor. However, this education did not captivate Darwin either; the lectures seemed as dull to him as his school lessons. His routine was enlivened by taxidermy (the hunter’s understandable interest in creating stuffed animals) and participation in the Plinian Society, where the natural history student encountered radical materialism and presented his first discoveries based on research of marine invertebrates.

Two years later, his father was disappointed to learn that his son had abandoned medical studies. The next attempt to educate Charles was at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where they trained Anglican priests. In this development, Darwin was pleased that attending lectures was voluntary, allowing him to spend time riding, shooting, hunting, and collecting insects. Among his finds were such rare specimens that they even made it into James Francis Stephens’ book “Illustrations of British Entomology.” This time, his passions did not hinder his studies: by 1831, Darwin had advanced in theology, literature, mathematics, and physics, ranking tenth among 178 successful students.

A Suitable Candidate for an Unpaid Position

After graduating, Darwin dreamed of studying natural history in tropical conditions. He read about it in the books of travelers who had visited exotic islands and began preparing for such an adventure: he took a geology course with Adam Sedgwick and participated in mapping rocks in North Wales. Upon returning from a summer expedition, Charles found a letter from a respected colleague in collecting, botanist and geologist, academic John Stevens Henslow. The English professor of botany and mineralogy informed him that he considered Darwin “a suitable candidate for an unpaid position as a naturalist” and recommended him to Captain Robert FitzRoy for a lengthy expedition to South America.

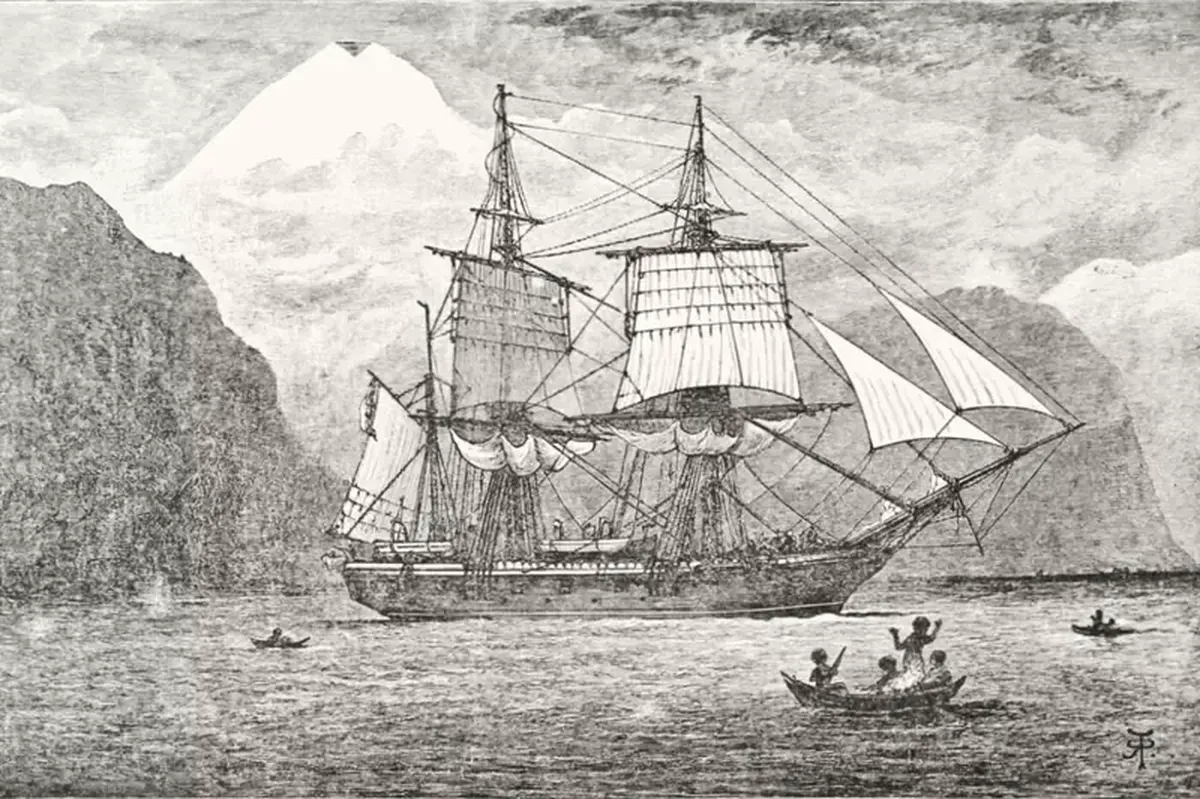

Darwin was to embark on a five-year voyage aboard the Royal Navy’s expedition ship “Beagle” in just four weeks, and he was ready to accept the enticing offer without hesitation. All he needed was his uncle’s help to convince his father to let him go for so long. In 1831, the university graduate set off on a round-the-world journey, returning to his homeland only in October 1836. During his scientific voyage, Darwin visited the Cape Verde Islands, the Galápagos Islands, Tenerife, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Tierra del Fuego, and Tasmania in Australia (the city of Darwin in Australia serves as a reminder of his time there), bringing back a wealth of interesting findings and observations, which he described in three books.

The Royal Navy ship “Beagle”

Man and Ape

On board the scientific vessel were three inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, whom the English had taken with them during the previous “Beagle” expedition and were returning home as missionaries a year later. Darwin saw them as friendly and civilized people, compared to whom the native tribes appeared “savage.” Their differences were as pronounced as those between wild and domesticated animals, the researcher noted, concluding that this was an example of cultural superiority, but certainly not racial inferiority. From then on, Darwin believed that there was no insurmountable gap between humans and animals, which facilitated his construction of the theory of common ancestors for humans and apes.

Even today, there are plenty of opponents to such a viewpoint among scientists and theologians, and at that time, Darwin faced an uncompromising adversary even on the ship. This was Captain FitzRoy, who later confessed that after meeting Darwin personally, he risked not taking him on the expedition due to… the shape of his nose. Seeing a connection between character and physical traits, the captain was convinced that a person with a round nose lacked the energy and determination necessary for such a journey, qualities he believed he possessed himself (Darwin suffered greatly from seasickness on the ship, but this did not prevent him from diligently conducting research that proved highly beneficial).

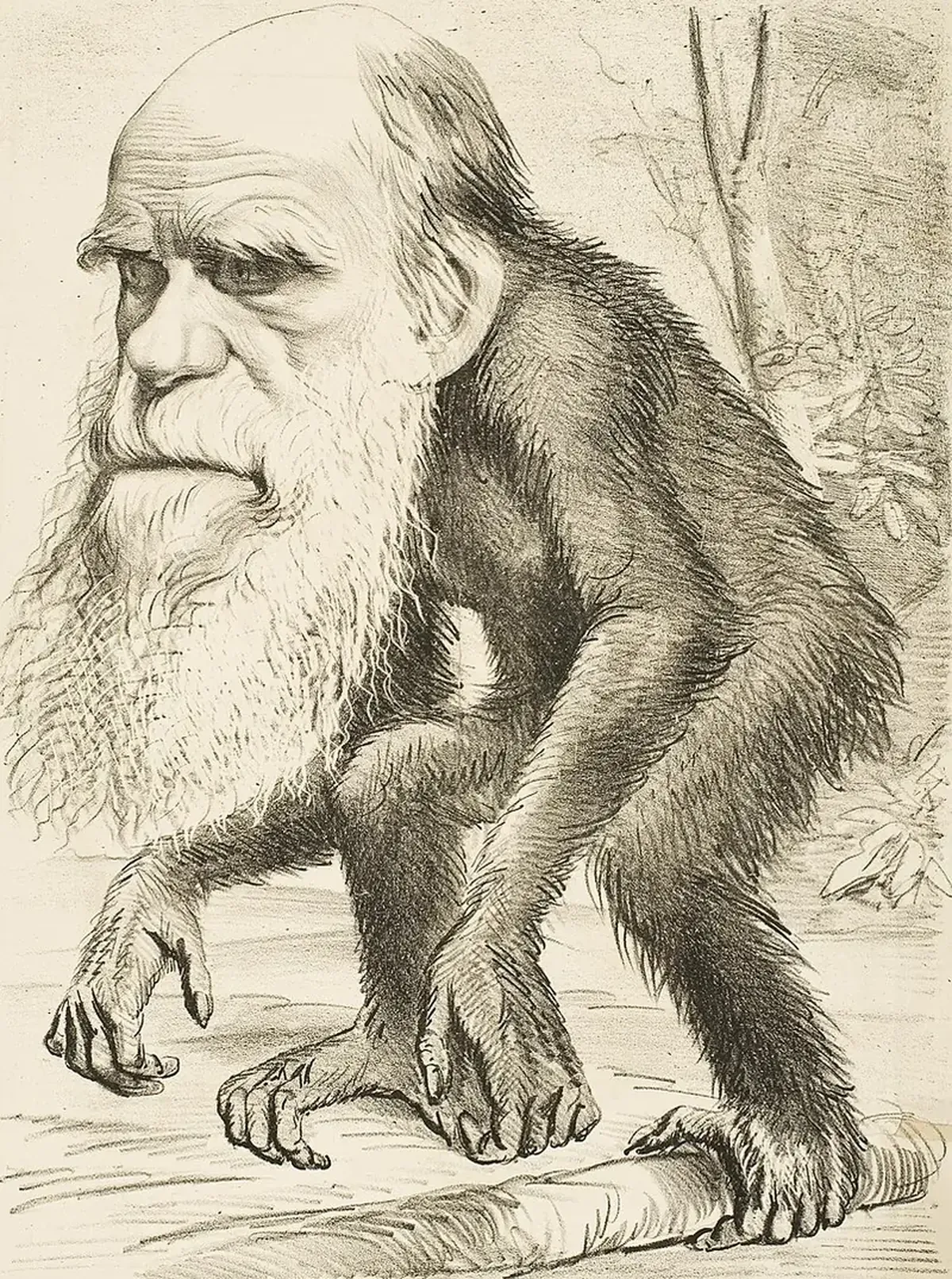

A caricature depicting Darwin with the body of an ape

The “Blasphemous Book”

In contrast, FitzRoy’s character, according to crew members, “was unbearable,” yet the captain possessed unrestrained energy, was brave, decisive, duty-bound, and generous. Darwin himself confirmed the nobility of the expedition leader and described his treatment of him as kind, but added that coexisting with the captain in close quarters, especially during meals in his cabin, was genuinely challenging: “We quarreled several times because in his irritation he was incapable of thinking.” FitzRoy commented on this: “My dining companion more than paid for his place on board the ship.”

The relationship was further complicated by serious political disagreements between the two men. While Darwin disapproved of British colonialism, FitzRoy justified slavery, being a staunch conservative and supporter of the English government’s colonial policies. FitzRoy’s religious dogmatism hindered him from accepting Darwin’s progressive views. The devout opponent did not share the scientist’s doubts about the immutability of species. In the future, he chastised Darwin for publishing such a “blasphemous book” as “On the Origin of Species,” in which the scientist was among the first to argue that all species of living beings evolve over time and descend from common ancestors.

Science and Religion

Darwin’s personal evolution involved a man trained as a pastor, knowledgeable in Anglican theology, which he studied at Cambridge, gradually beginning to question the truth of the Bible. While after studying the philosophy of Christian apologist William Paley, who advocated for intelligent design in nature as proof of God’s existence, Darwin fully agreed with this, after his journey on the “Beagle,” his views began to diverge from the “obviously false history of the world” presented in the Old Testament.

After returning, the researcher began secretly gathering evidence of species’ variability, understanding that his fellow naturalists would consider such work “subversive.” Darwin continued to support the local church and assist parishioners in communal affairs, but instead of attending Sunday services, he would go for walks. Although the naturalist identified as an agnostic, his religious views shifted toward atheism. In 1868, he wrote that “it cannot be asserted that religion is not opposed to science,” and speculated that “for people of science, it might be wisest to completely ignore religion.”

The “Detestable Doctrine”

If earlier Darwin viewed religion as a tribal survival strategy, the gradual realization of his disagreement with the concept of creationism—which does not deny the possibility of biological development but considers divine intervention as the trigger for such evolution—led Darwin to conclude that Christianity deserves “no more trust than the beliefs of savages.” The naturalist’s doubts grew stronger each time he observed a wasp paralyzing a caterpillar that would become live food for its larvae. Ultimately, faith in an all-good God left Charles Darwin with the death of his ten-year-old daughter Annie (the girl died in 1851).

“Thus, doubt gradually crept into my soul, and eventually, I became a complete unbeliever,” the scientist wrote in his “Autobiography.” “Since this process was extremely slow, I felt no distress and never doubted the correctness of my views for a moment. After all, it is indeed difficult to consider a simple text (referring to the Gospel) as truth, regardless of how one relates to the Christian doctrine, which shows that non-believers—among whom my father, brother, and almost all my close friends should be included—are destined for eternal punishment. A detestable doctrine!”

Did He Suffer from a Beetle?

After his journey on the “Beagle,” Darwin fell ill. He stopped going out and communicating in public. In the past, it was assumed that the scientist avoided mass gatherings and scientific debates out of fear of facing critics. However, later, the scientist’s reclusiveness began to be associated with panic attacks stemming from an unclear diagnosis. Painfully aware of his condition, Darwin wrote to a botanist friend that “to share one’s guesses is like confessing to murder.” In his diary, Darwin described symptoms such as depression, weakened immunity, rashes, eczema, boils, mouth ulcers, gum and tooth problems, joint pain, nausea, frequent vomiting, abdominal pain, palpitations, intense headaches, and insomnia.

The scientist’s son, Francis Darwin, testified that “for forty years, my father never felt completely healthy, and his entire life was a struggle with the stress and exhaustion caused by illness.” It is known that at the age of nine, Charles contracted scarlet fever (he had no vaccinations, although his famous grandfather Erasmus Darwin was a pioneer of immunization), and skin problems and stomach pains were also familiar to him from childhood. Analysis of family documents confirmed modern doctors’ assumptions that the naturalist’s poor health had both organic and hereditary causes. Among the two dozen hypotheses proposed were lactose intolerance and Chagas disease, endemic to Latin America (the pathogen affects the small intestine and is transmitted by a bug that may have bitten the scientist). Against this backdrop, the sick man took many medications with toxic effects, including arsenic, bismuth, quinine, and morphine.

How Many Children Did Darwin Have?

From 1838 to 1841, while serving as secretary of the London Geological Society, Darwin married his cousin Emma Wedgwood. Initially, the couple lived in London, but in 1842 they moved to Down. In Kent, the head of the family led a secluded and quiet life as a scientist and writer, adhering to a schedule that allowed him to remain productive despite his physical weakness. Unfortunately, Charles Darwin’s descendants were also often sickly or weak. The naturalist had ten children, three of whom died in childhood. He attributed this to his close kinship with his cousin-wife. His conclusions about the health issues of descendants from close kinship and the advantages of distant interbreeding are reflected in his works.

Emma Wedgwood and Charles Darwin

Nevertheless, many of Darwin’s children and grandchildren became successful individuals. Among his sons were a banker, a botanist, a mathematician and astronomer, the head of the Royal Geographical Society, an engineer, and the mayor of Cambridge. Charles Darwin himself passed away on April 19, 1882, and was laid to rest in recognition of his contributions at Westminster Abbey—the London pantheon of distinguished figures from Great Britain. In honor of the scientist, two awards were established: the Darwin Medal and the Darwin Plaque, which are awarded annually by the Royal Society of London for outstanding achievements in biology and the fields of science in which Charles Darwin worked.