According to a study from Imperial College London, children from poorer families are more likely to face biological issues, such as accelerated aging, compared to those born with a silver spoon in their mouths.

A team of researchers analyzed data from 1,160 children aged 6 to 11 across Europe. Participants were assessed using an international wealth scale based on various indicators, such as whether the child had their own room and the number of vehicles in the family.

How Was the Study Conducted?

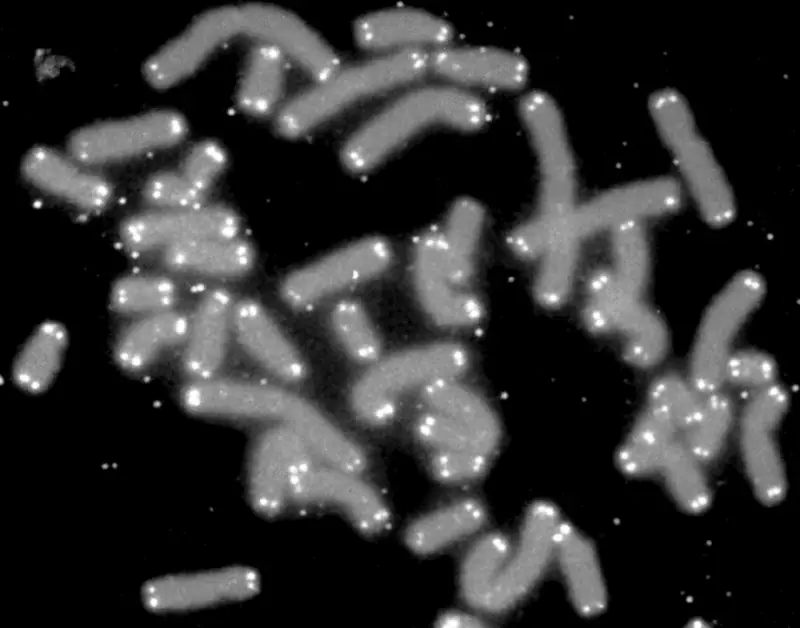

The scientists divided the children into three groups based on high, medium, and low family wealth. They then took blood samples from the participants to measure telomere length.

Telomeres are structures in chromosomes that play a crucial role in cellular aging and DNA integrity. In simple terms, telomere degradation is linked to aging: as we age, telomeres shorten, as noted by The Guardian.

Previous studies have suggested a connection between telomere length and chronic diseases, as well as the idea that acute and chronic stress contribute to telomere shortening.

The results showed that children from the wealthiest group had telomeres that were, on average, 5 percent longer than those from the poorest group. In girls, telomeres were longer than in boys by an average of 5.6 percent. Meanwhile, children with a higher body mass index had telomeres that were shorter by 0.18 percent for each percentage increase in body fat.

The researchers also found that children from low-income families had cortisol levels—the stress hormone—that were 15.2 to 22.8 percent higher than those of wealthier children.

Key Takeaways

Thus, the study confirmed a link between financial status and telomere length, which is known to be associated with lifespan and health.

Dr. Oliver Robinson, the lead author of the study, stated, “Our results demonstrate a clear connection between family wealth and a well-known marker of cellular aging, with potentially lifelong patterns being established in the first decade of a child’s life. This means that economic conditions can place some children at a biological disadvantage compared to those who have a better start in life. As a result, we are directing children onto a lifelong trajectory where they are more likely to have less healthy and shorter lives.”

He added, “Belonging to a low-income group causes additional biological wear and tear.” This could be equivalent to “approximately 10 years of cellular aging compared to well-off children.”

Kendall Marston, the first author of the study, noted, “We know that chronic stress exposure leads to biological wear and tear on the body. This has been demonstrated in animal studies at the cellular level—stressed animals had shorter telomeres.”

“It’s likely that children from less affluent families experience higher stress levels. For example, they may have to share a bedroom with other family members or lack the resources needed for school, such as access to a computer for homework,” Kendall Marston pointed out.

The study’s findings were published in The Lancet.