However, her ideas felt constrained within a single movement. Her boundless creativity constantly sought new niches for expression.

However, her ideas felt constrained within a single movement. Her boundless creativity constantly sought new niches for expression.

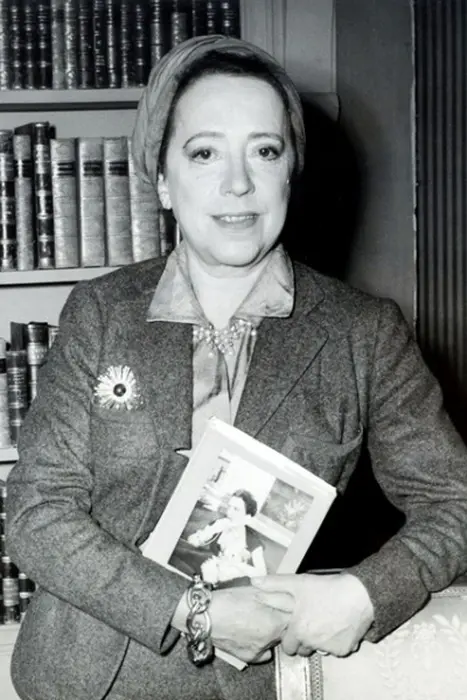

If Elsa Schiaparelli (1890 – 1973) didn’t exist, we would have to invent her. Because without her, the world would be a duller place. She seamlessly integrated into the interwar era, which became a time of flourishing for her. Elsa infused it with extravagance and novelty.

The dresses, hats, bags, and perfumes of Schiap (as her friends called her) demonstrated to the mundane world that fashion is not just clothing that breathes in rhythm with time; it is also provocation, mischief, and play.

Born into a wealthy family of Roman aristocrats, Elsa Louise Maria Schiaparelli had a great start for her future self-expression.

Scientist relatives, a thirst for knowledge, intellectual training, a love for art and literature, refined taste, a passion for innovation, adventurousness, and, of course, exceptional talent: this is just a partial list of the factors that shaped Elsa into who she became.

Fashion chroniclers often recall the incident when young Elsa, inspired by ancient myths, wrote rather risqué poetry. In response, her educated but conservative parents sent her to a convent boarding school in Switzerland. Elsa’s rebellious nature resisted the educational system there (and later any system that tried to standardize individuality). It’s no surprise that soon her parents had to bring her back home.

Elsa Schiaparelli in childhood

From an early age, she understood what she hated most and what she would never be. She despised the stifling world around her and could never be ordinary—in every sense of the word.

Schiap sought not only to match herself but to surpass herself. Ultimately, she opened a fashion house in Paris that gained worldwide fame. She was the first among designers to collaborate with artists. Fashion historians often cite her creative partnership with the genius of surrealism, . Among those who also became part of her circle of inspiring friends were Jean Cocteau, André Breton, Alberto Giacometti, and . Additionally, Elsa became a favorite designer of Hollywood stars. She dressed , Katharine Hepburn, Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, and Mae West. Schiap attracted like-minded individuals.

Elsa Schiaparelli with Salvador Dalí

Tests of Resilience

Long before Elsa Schiaparelli began creating outrageous clothing and accessories, fate repeatedly tested her resilience. And even afterward, it didn’t let up.

The first such trial was related to the appearance of little Elsa, who was not considered beautiful in her family. The girl, fascinated by the beauty of flowers, once gathered seeds and sprinkled them on her face, nose, and mouth, hoping that flowers would grow and grant her their beauty. Instead, Elsa nearly suffocated.

But more than anything, she suffocated from the impossibility of being herself in her “golden cage”—her parents’ palazzo. As pompous as that sounds, even then, Elsa felt that the time to express herself was approaching, though she didn’t yet know what those expressions would be.

Eventually, one day, the girl broke free from her family nest and headed to London to work as a governess.

The next test of fate was her marriage to the 30-year-old theosophist and psychic, Count Willem de Wendt, who turned out to be a charlatan and a womanizer. When the couple married, the girl was 23 years old. With her husband, Elsa traveled to America, where she gave birth to a daughter, Yvonne Maria Louise (nicknamed Gogo by family). Perhaps this was the only event that somewhat redeemed the count’s deceitful presence in Elsa’s life, as he soon distanced himself from her. The couple divorced, leaving Schiaparelli without means of support and with a sick daughter in her care. She tried to stay afloat, taking on any job available. Ultimately, in 1922, she returned to Paris, where her rapid ascent into the world of fashion—the main pursuit of her life—began.

Elsa Schiaparelli with her daughter, 1938

One could lament that Elsa spent nearly a decade not on innovative developments but on futility. Or one could take comfort in the thought that nothing is given by fate without reason. The survival skills and hard work she honed would prove invaluable when she became famous, and her portrait graced the cover of Time. For instance, during World War II, while evacuating to America from occupied Paris, Elsa worked at a Red Cross hospital as a nurse and surgical assistant.

Another significant test of Schiap’s resilience was her rivalry with : contemporaries of the renowned designers referred to this confrontation as a “civil war.” However, it was usually noted that Coco was the aggressor and master of intrigue, while Elsa responded with dignity. The reason for their irreconcilable differences lay not only in the fact that the two couturiers competed for high-profile clients but also in their vastly different aesthetics. Chanel, classically restrained in her designs, could not accept the avant-garde antics of her competitor and condescendingly referred to Elsa as “the Italian artist who makes clothes.”

A Shocking Star in the Fashion Firmament

Between the First and Second World Wars, the concentration of top-tier creators was off the charts. Perhaps this was the era’s response to the hypertrophied pain that silences strings, pencils, and paints.

The interwar period seemed to strive to unleash as many incredible people with extraordinary ideas as possible. It was the time of the eccentric visionary Schiaparelli, who did not conform to rational, colorless reality but instead adapted it to her whims and painted it in vibrant hues.

The color pink, often seen as vulgar by her contemporaries, took on bohemian sophistication in Elsa’s interpretation. Her signature shade became “shocking pink,” now known as fuchsia.

For Schiap, fashion was the realm in which she felt liberated—as an artist and as a model. “Although I am very shy (no one believes this), so shy that the simple necessity of greeting someone sometimes leaves me paralyzed, I have never been afraid to step out in the most original outfit I designed myself,” Elsa wrote in her memoirs, titled “My Shocking Life” (1954).

As she attended Parisian social gatherings, Schiap increasingly felt that she could offer fashion enthusiasts a bolder approach to clothing. But to bring this plan to life, she needed a push. The renowned designer Paul Poiret, with whom Schiaparelli met by chance, became the inspiration for her future projects. He was one of the first to positively evaluate the clothing sketches she had been drawing “for herself.” He even asked her to model clothes from his collections.

It was likely thanks to Poiret that Elsa became fully convinced that she needed to promote her ideas, even if they seemed crazy to a narrow-minded public. However, something meaningful can only emerge from an artist when they trust their instincts and disregard the reactions of detractors.

In 1927, a year associated with the beginning of Schiaparelli’s brand establishment, she achieved her first success with a knitted pullover featuring an imitation white bow depicted at the neck. The model, created by a knitting master based on Elsa’s design, caught the attention of Parisian fashionistas. Schiap unexpectedly received an order for two dozen of these items—the first in her life as a creative Italian in the role of a fashion designer. Moreover, one of these pullovers made it onto the pages of Vogue that year.

Soon after, she founded her own sportswear salon, a place where her incredible ideas received real embodiment and paved their way into life. One of Elsa’s revolutionary designs was a slap in the face to conventional morality, which deemed considerations of practicality and comfort irrelevant. The designer created cropped skirt-pants for female tennis players. This caused a scandal among those who preferred to keep the so-called “weaker” sex in a black body.

Her nature could not reconcile with the fact that most women tried to remain unnoticed and therefore dressed in something gray. “It’s better to have the courage to stand out from the crowd,” Schiap believed. She wrote: “I firmly believe that women have the right to express themselves in any way they choose. I have always advocated for women’s liberation and sought to create fashion that reflects this spirit.”

The House of Schiaparelli: The Beginning of Flourishing and Blooming

Thus, Elsa designed unexpected and comfortable models for sports competitions while simultaneously building plans to create clothing that would conquer the world. At the same time, she was keenly interested in bohemian Paris, where new names of the creative Olympus sparkled one after another.

In 1934, within the walls of a former 17th-century hotel at 21 Place Vendôme, the House of Elsa Schiaparelli opened its doors: a space with nearly 100 rooms housing a salon, boutique, and workshops.

The house embodied a rejection of boredom, monotony, and conformity. It became the realm of Schiap’s endless creativity, where she produced her ideas. Often, these ideas awaited completely unexpected embodiments. As Picasso wrote, “I start with an idea, and then it becomes something else.”

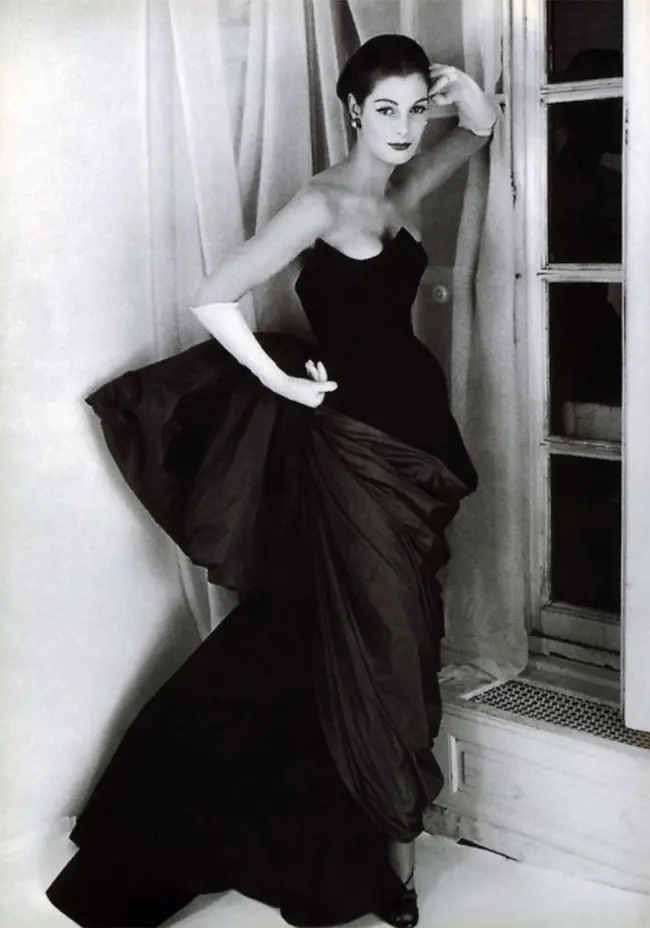

In her artistic laboratory, Schiaparelli focused on themes of knitted swimsuits, sportswear, and evening gowns. The imaginative Elsa experimented with new materials, prints, colors, shapes, and whimsical decorations, unafraid of being accused of kitsch. She transformed themed collection shows into eccentric spectacles.

Moulin Rouge with Zsa Zsa Gabor, for whom Schiaparelli created costumes

Not knowing how to sew, she often created dresses by draping fabrics directly on her body. It was through her innovative approach that the aforementioned skirt-pants, bathrobe dress, newspaper print (the first she made from reviews about herself), decorative zipper, bikini cups, and shoulder pads entered the arsenal of fashionistas in subsequent generations. The luxury in her pieces had a Hollywood flair. It’s no wonder that Schiap signed contracts with leading film studios, designing costumes for movies and personal outfits for actresses.

Purse and powder compact created with Salvador Dalí

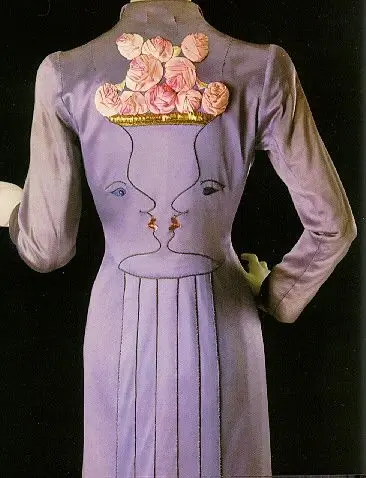

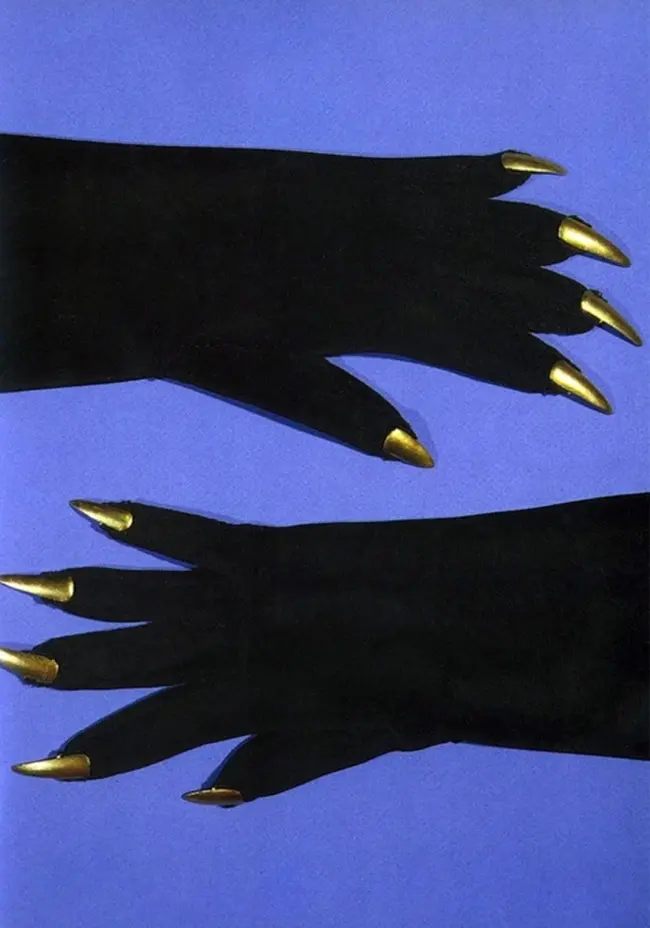

At this stage, Elsa’s collaboration with artists received new life. Notably with Salvador Dalí, who was destined to cross paths with Elsa. They were two kindred spirits. It’s hard to say who inspired whom more. But this partnership produced many intriguing creations, such as the shoe hat with the heel pointing upward, the “Lobster” dress for Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, the skeleton dress, the telephone bag, gloves with fake nails, the “Tears” dress with an imitation of torn patches of skin, a suit with drawer pockets, and the design of her most famous perfume, “Shocking!”, whose bottle in the shape of a female torso echoed the forms of Mae West.

Perfume ‘Shocking!’

Interestingly, Schiap banned the word “creativity” in her fashion house, considering it “the pinnacle of pretentiousness.” The word “impossible” was also taboo, as Elsa demanded perfectionism from her team, which she viewed as the primary motivator.

In Place of an Epilogue

Returning to Europe after World War II, Elsa Schiaparelli, like many others who made a rapid career between the wars, could not regain her former glory in the new harsh reality. Fashion had changed entirely. In 1947, released the New Look collection, marking a revolutionary shift in the perception of clothing. Now, the silhouette featured a narrow waist and a voluminous skirt. Such clothing for women was costly—due to the meters of fabric used—and not very comfortable—due to the need to be laced back into a corset. However, the times dictated their own conditions for existence in society.

Elsa Schiaparelli, 1953

Schiap closed the doors of her fashion house in 1954. The last stage of her life was spent between Paris and Tunisia, dedicating herself to raising her two granddaughters. In 1973, at the age of 83, Elsa Schiaparelli completed her earthly journey. She was buried in a “shocking pink” pajama.

Perhaps the tireless inventor Schiap would have been delighted to learn that in the 21st century, her fashion house was revived. More than half a century after its closure, in 2007, Italian entrepreneur Diego Della Valle purchased the rights to the Schiaparelli brand from the designer’s descendants. To restore the brand to its former glory, he enlisted Christian Lacroix. After the renowned designer, several of his colleagues took on this noble endeavor. Eventually, the house once created by Elsa Schiaparelli finally joined the Syndicate of Haute Couture. In 2019, Daniel Roseberry became the creative director of the house.

We must give credit to Schiap’s successors; they have all strived to preserve the surreal spirit of Elsa, which likely still wanders the ancient corridors of the building on Place Vendôme.

Click on any photo to open the full gallery of stunning dresses by Elsa Schiaparelli with large images.