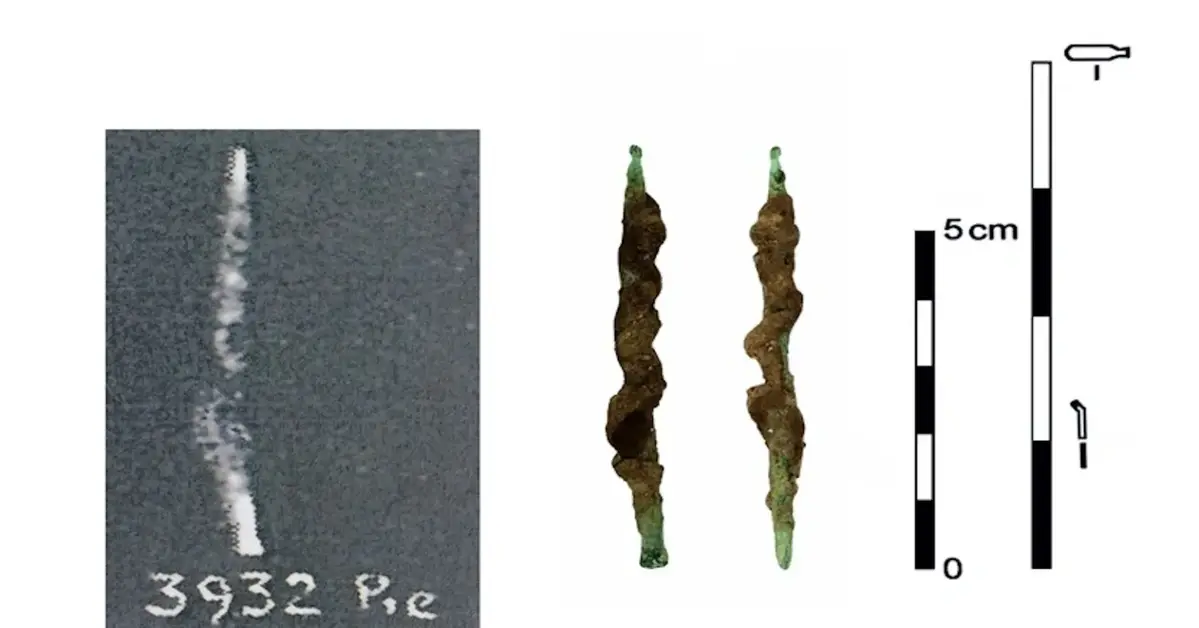

Nearly a century ago, archaeologists excavating a cemetery in Upper , dating back to the late 4th millennium B.C., discovered a small, hard-to-identify in the grave of an adult male. Although experts confidently classified the find as belonging to the predynastic period, the purpose of the object, measuring approximately 2.5 inches (about 6.3 cm) in length, remained unclear.

Nearly a century ago, archaeologists excavating a cemetery in Upper , dating back to the late 4th millennium B.C., discovered a small, hard-to-identify in the grave of an adult male. Although experts confidently classified the find as belonging to the predynastic period, the purpose of the object, measuring approximately 2.5 inches (about 6.3 cm) in length, remained unclear.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge eventually described it as “a small copper awl with a leather strap wrapped around it” and placed it in storage at the university’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. This was reported by Popular Science.

A Century-Long Mistake: Why We Underestimated Ancient Craftsmen

However, a careful reanalysis shows that this “awl” is far more significant than previously thought—so much so that it could rewrite the history of Ancient Egypt. In a study published in the journal Egypt and the Levant, a team led by Newcastle University archaeologist Martin Odler argues that the object is actually the oldest known example of a bow drill in the region. If this is true, the creation of this tool dates back more than 2,000 years earlier than previously believed.

“ are known for their stone temples, intricately painted tombs, and dazzling jewelry, but behind these achievements were practical, everyday technologies that rarely survive in the archaeological record,” Odler explained in a statement. “One of the most important was the drill—an essential tool for boring into wood, stone, and beads, enabling everything from furniture making to jewelry crafting.”

Original photograph of the artifact published in 1927, along with the artifact itself

Secrets of an Ancient Alloy and Networks of Knowledge

Analysis using X-ray fluorescence revealed that the tool was made not from pure copper, but from a more complex alloy. It contained arsenic and nickel, along with traces of lead and silver.

At first glance, this may seem coincidental, but for archaeologists, such a “mix” of metals is an important clue. Pure copper is relatively soft, causing tools made from it to dull quickly. The addition of arsenic or nickel makes the metal harder and more durable, making it more suitable for drilling or working with tough materials.

This leads scientists to suggest that the composition of the alloy may have been intentionally selected. This implies that craftsmen of the time already understood the properties of metals and could experiment with additives to achieve the desired results. If so, the technological knowledge of the ancient Egyptians was far more advanced than previously thought.

Moreover, such a metal composition may indicate contacts with other regions of the Eastern Mediterranean, from where ores or finished metal blanks could have been sourced.

A Revolution in Craftsmanship Long Before the Pyramids

Prior to this reevaluation, bow drills had only been documented in later periods of Egyptian history, such as during the New Kingdom in the mid to late 2nd millennium B.C. Evidence of this can be found in wall paintings in on the west bank of Luxor, depicting craftsmen making beads and wooden items.

“This reanalysis provides compelling evidence that the object was used as a bow drill, which allowed for faster and more controlled drilling than simply pushing or twisting an awl by hand,” Odler added. “This means that Egyptian craftsmen mastered reliable rotary drilling more than two thousand years before some of the best-preserved sets of drills appeared.”