The countries where he was born and died— the Holy Roman Empire and the Austrian Empire— no longer exist, yet Beethoven’s name in the 21st century means no less than it did in the 18th. Though deaf to notes, the genius masterfully played several instruments, composed symphonies, and conducted orchestras. Deprived of physical hearing, fate left him with musical hearing, enough to create immortal masterpieces across all genres.

Not the Second, but the First

He did not become the “second Mozart” as his parents wished, but instead became the “first Beethoven.” The great Austrian predecessor, upon hearing his unique successor in Vienna, predicted the world would come to know him. And so it happened, during the legendary composer’s lifetime. He lived only 56 years, 30 of which were spent in profound silence, alone with his inner tuning fork. Paradoxically, those years became the key to his unparalleled creativity, when he gifted humanity his greatest symphonies, opera, choral works, theatrical music, sonatas, overtures, quartets, and concertos.

One of the most interesting classical music composers for performers of all times and nations gave the piano its own “voice,” allowing it to differ from the harpsichord. This legendary German composer created the “signature” piano style, featuring dramatic contrasts between extreme registers (while harpsichord playing was limited to the middle registers), forceful volume and depth (previously, continuous use of the pedal was uncommon), and powerful chordal harmony.

Son of a Tenor, Grandson of a Bass

The phenomenal child was born on December 16, 1770, in Bonn — into a family of hereditary musicians. Ludwig was named after his grandfather (a native of the Southern Netherlands) who rose to head the court chapel in the Archduchy of Austria. The composer’s parents were singers in the court chapel: the grandfather was a bass, the father a tenor (the mother was the daughter of the court’s head chef).

From a tender age, young Ludwig was introduced to the violin, organ, and harpsichord, and by 8 years old he gave his first public performance in Cologne. Teachers encouraged the talented pupil to perform “well-tempered clavier” works, so young Beethoven grew up on the notes of Bach, Mozart, and Haydn. By 12, the assistant court organist’s repertoire already included his first original piece: variations on a famous march theme. In childhood, Ludwig van Beethoven composed three sonatas and a number of songs, one of which — “The Groundhog” — is still studied by children in schools today.

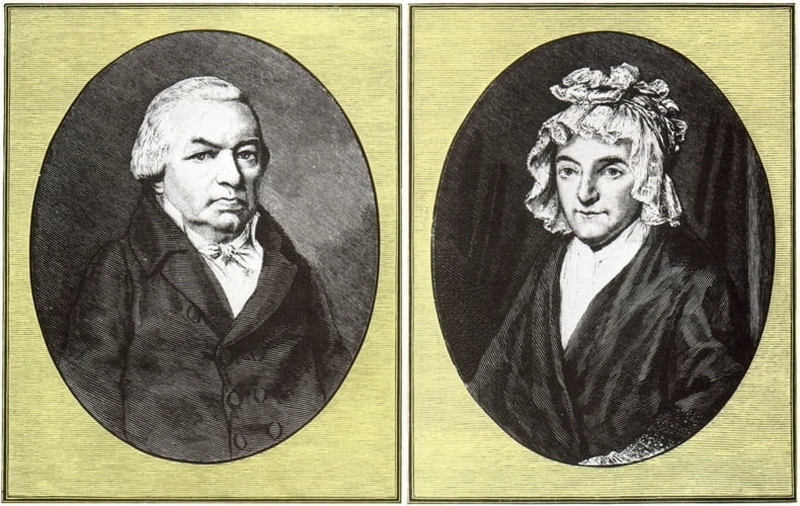

Beethoven’s parents: Johann and Maria Magdalena

Due to the family’s worsening financial situation after his grandfather’s death, Beethoven had to leave school early and educate himself. Besides music, he was passionate about literature, languages, and philosophy: he read German, French, Italian, and Latin, striving since childhood, as he said, to understand the essence of teachings from the most famous sages of various eras. His literary baggage included works by Homer, Plutarch, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller — none of which he found too difficult.

Titles Are Not Achievements

Beethoven never got to study with Mozart. Impressed by the young man’s improvisation (“Everyone will talk about this boy!” said Mozart in 1787), 17-year-old Ludwig left Vienna due to his mother’s death. Caring for his younger brothers left little time for study; he took a position as a violist in an orchestra where he played pieces by a potential teacher. Within two years, he resumed formal study.

He attended lectures at the University of Bonn amid the upheaval of the French Revolution. As was common, the progressive university professors supported “leftist” ideas, and Beethoven, inspired by a professor’s collection of revolutionary poems, composed a work on social justice. His “Song of the Free Man” contained the phrase: “Free is he who does not regard birth or title as a privilege.”

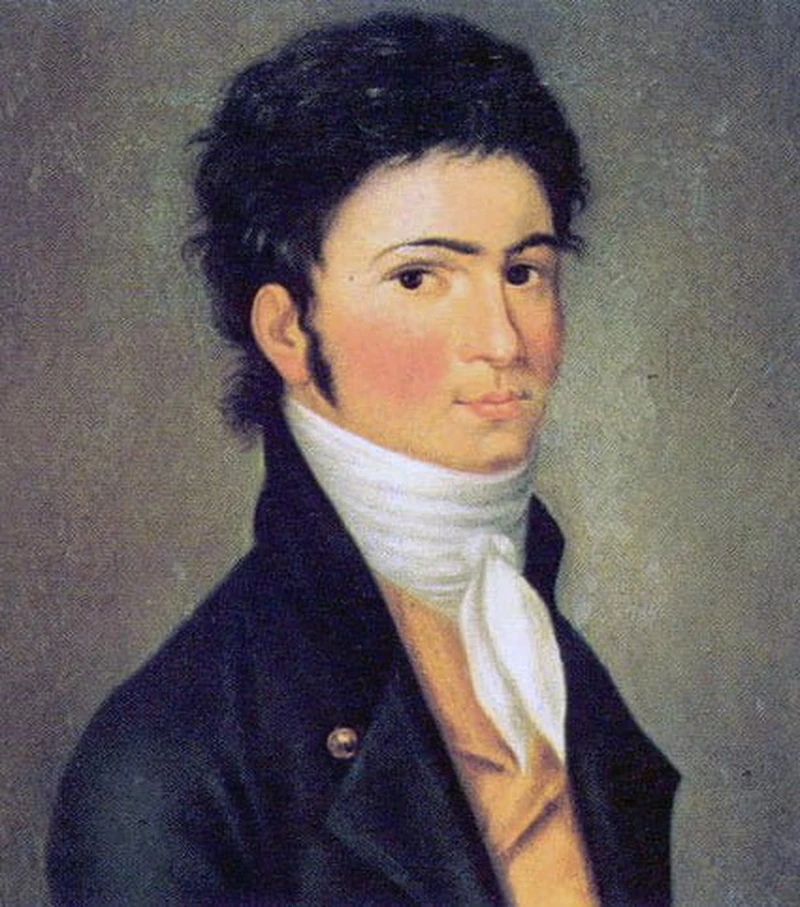

Young Beethoven (1801), painting by Karl T. Riedel

In this sense, Beethoven considered himself free. He allowed himself not only informal hairstyles and sloppy clothes but also sharp judgments and independent behavior. He stopped performances due to talking in the hall: “Do not cast pearls before swine.” He refused requests from hosts to entertain guests if he himself was among them. When high-ranking Prince Lichnowsky announced Beethoven’s performance at his salon, the unyielding composer left the room and locked himself away. The prince ordered the door to be broken down, and Beethoven slammed the door loudly, immediately leaving the aristocrat’s palace, offended by him. The next morning, Beethoven sent Lichnowsky a note: “I owe my name to myself. There are many princes, but only one Beethoven.”

There Is No Harmony in the World

Even when he met Emperor Franz on the street, Beethoven did not bow respectfully but pushed aside, according to Goethe’s memoirs, the crowd of servants, barely touching his hat. After Napoleon’s disdain for the ideals of the French Revolution, the disillusioned 34-year-old Beethoven refused to dedicate his “Third Symphony” to the self-proclaimed emperor. He scratched the dedication off the title page near the name “Eroica” and explained his decision with a bold accusation: “Now this ordinary creature tramples on civil rights and will become a tyrant.”

Title page of the ‘Eroica’ Symphony, edited by the composer

Colleagues had to burn part of the “conversation notebooks” used to communicate with deaf Beethoven because of his harsh criticism of the emperor, the heir prince, and other rulers. The composer constantly criticized anti-people policies, unjust laws, and outrageous decrees. “You’ll end up on the scaffold,” friends warned, sometimes alerting him to spies in their company. Beethoven’s pessimistic worldview inevitably influenced his personality and work, which sometimes alienated people. For example, Haydn called his student talented but “gloomy and strange” and refused to work with him due to radical views.

Who Killed the Genius?

Despite his stern exterior, Beethoven never refused help to relatives and friends in need. He barely overcame suicidal thoughts caused by early deafness (he began losing his hearing at 26, and as research on his remains in 2007 showed, “lead compresses” from puncturing his abdomen to drain fluid by Beethoven’s doctor may have worsened the condition). He found the strength to live on—for a purpose he saw in creating music and supporting loved ones.

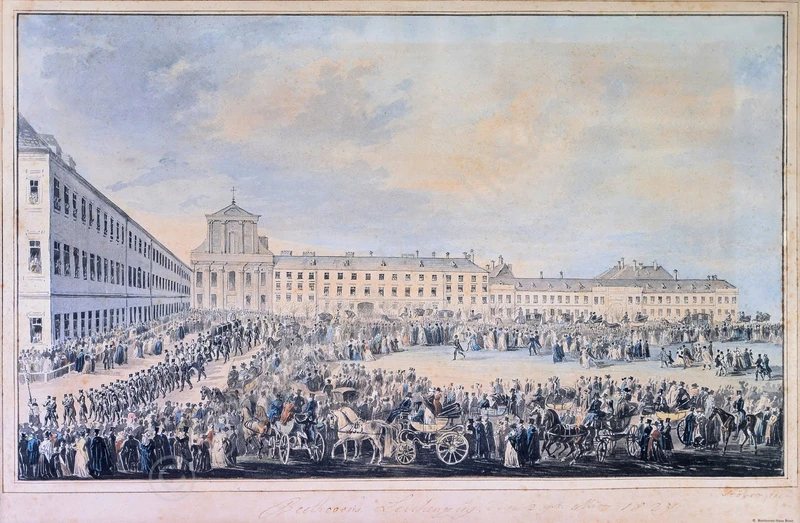

After his brother’s death, Beethoven took care of his nephew. How the nephew misused this support destroyed Beethoven’s health. The ungrateful young man was more interested in billiards and cards than art: he went into debt and attempted suicide. A bullet left a scratch on the nephew’s head, and Beethoven’s sick liver failed from stress. Beethoven died in March 1827, aged 56. Twenty thousand admirers of his immortal music attended his funeral.

Beethoven’s funeral procession: watercolor by FX Stoeber