Despite examples of more effective spies in the 20th century, the archetype of the femme fatale has been immortalized in countless films, series, musicals, and novels. This character, who was exploited by two intelligence agencies during World War I, met her end at the age of 41 by firing squad. Behind the tragic fate of this darling of the European elite lay a difficult childhood, a troubled marriage, dramatic motherhood, and a struggle to understand the role she was destined to play in the events shaped by history.

Mata Hari – Who Was She?

The real name of the performer of “adult dances,” akin to modern-day striptease, was Margaretha Gertruida Zelle. She was born in the Netherlands on August 7, 1876. The only daughter of Adam Zelle and Antje van der Meulen, she grew up with her three brothers. Her father owned a and earned income from successful investments in oil extraction. The family was well-off, so for a time, the children lacked for nothing, and Margaretha attended elite schools until she was 13. Everything changed after her father’s bankruptcy in 1889. Soon after, her parents divorced, and her mother died of tuberculosis two years later.

In 1891, her father sent his 17-year-old daughter to another city to live with her godfather in Sneek. Continuing her education in Leiden, young Margaretha planned to become a kindergarten teacher. However, her godfather had to withdraw her from school due to an inappropriate flirtation with the director’s daughter. A few months later, Margaretha left her guardian, fleeing to The Hague to live with her uncle, and at 18, she married a 39-year-old Dutchman of Scottish descent, Captain Rudolf MacLeod, whom she met through a personal ad. After registering their marriage, the couple moved to the Dutch East Indies.

Margaretha with her husband, Captain Rudolf MacLeod

What Does Mata Hari Mean?

On the island of Java in Indonesia, Margaretha gave birth to two children: a son, Norman-John, in 1897, and a daughter, Jeanne-Louise, in 1898. However, the family was far from happy. Rudolf, who struggled with alcoholism, often took out his frustrations on his young wife due to his disappointments in life and career. The much older man not only cheated on her repeatedly but also flaunted his mistresses and kept several women. Disillusioned with her marriage, Margaretha left her husband for another Dutch officer and sought to earn her own income. She joined a dance troupe, began studying Indonesian culture, and immersed herself in local dance traditions.

In 1897, Margaretha adopted the stage name Mata Hari, which translates from Malay as “eye of the day” and means “sun.” In Eastern dance, she found solace after family quarrels (her husband persuaded her to return, but his aggressive behavior did not change) and the tragic death of her two-year-old son. The child may have been poisoned by a vengeful maid, as Rudolf had conflicts with her husband. However, another theory suggests that the child’s death was due to complications from syphilis, which the parents had passed on to their children. Their daughter also died from this diagnosis at the age of 21 (Rudolf took custody of her after their divorce in 1903).

The Capital of Erotica

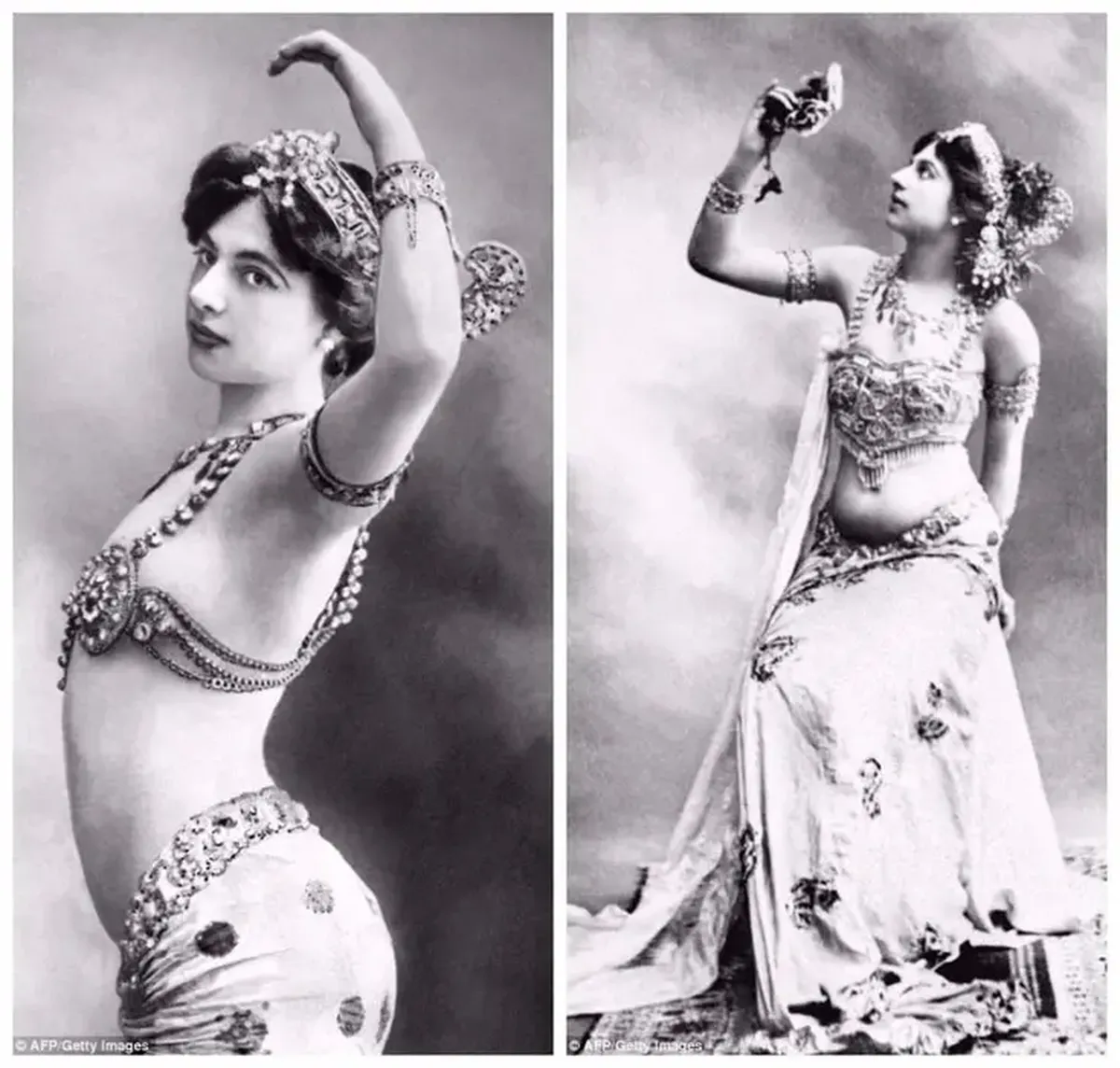

After returning to the Netherlands, Margaretha MacLeod-Zelle found herself in poverty and decided to head to Paris, where she could earn a living with her artistic skills and captivating stories. Initially, the striking Dutchwoman performed in a circus as an exotic rider under the name “Lady Grisha MacLeod,” claiming that her unusual horse could only be ridden by her. By 1905, she had enchanted French audiences as a dancer of “Eastern style”: the early 20th century was marked by a lively interest among Europeans in the East. Her exotic name on posters attracted not only fans of Eastern dance but also men looking for entertainment.

Thus began the stage career of Mata Hari. In the “capital of romance,” Paris, and later in other European capitals, performances based on ballet and eroticism became popular. Mata Hari’s shows featured spectacles that were unfamiliar to Western audiences, where the dancer would almost completely undress by the end of her performance. Claiming to perform sacred dances of the East that she had learned in childhood, Mata Hari undressed for money, as it was “pleasing to Shiva.” There was no shortage of mystification in her performances: the dancer presented herself as a student of a Buddhist monastery or an Eastern princess (the daughter of an Indian prince and King Edward VII).

Between Erotica and Politics

The experiences of male cruelty, violence, poverty, and harassment in the dance world led Margaretha to the profession of a courtesan. Her charming persona was sought after for romantic encounters by high-ranking officials, politicians, and influential figures in France, Germany, and other countries where she performed. Margaretha squandered her easy earnings in gambling: she became an avid card player and was perpetually in debt. Overall, she had connections and weaknesses that allowed intelligence agencies to recruit her for espionage activities. It is likely that Mata Hari became a German spy long before the war began.

However, the exact circumstances of the dancer’s recruitment remain unclear. Since the Netherlands was a neutral country during World War I, its citizen Margaretha Zelle could travel freely between France and her homeland. However, these journeys could not be made through German-occupied Belgium, where battles were raging, but rather through Spain (a country with an active German residency at that time) and Great Britain. These movements did not go unnoticed by Allied counterintelligence. In 1916, French intelligence began to suspect Mata Hari’s involvement in espionage for Germany.

Mata Hari with her Russian lover Maslov

Double Agent

Upon learning that the French counterintelligence had compromising information on her, the courtesan dancer approached the agency herself, offering her services: she was willing to become a French spy. During her discussions with them, Mata Hari carelessly mentioned the name of her lover, known to the French as a German recruiter. The French intelligence sent the Dutch woman on a verification mission to Madrid and confirmed their suspicions of her being a double agent working for Germany. According to intercepted radio messages from a German agent in Spain, the other side was informed that the French-recruited agent H-21 had arrived in Madrid and was returning to Paris.

An analysis of the events suggests the possibility of deliberate disclosure of the radio interception by the German residency to eliminate the double agent and hand over the spy to the opposition. A photo of Mata Hari taken on February 13, 1917, marked her arrest immediately after her arrival in Paris. The Dutch national Margaretha Zelle was charged with espionage. She was accused of passing information to the enemy during wartime that led to the deaths of several divisions. The materials from the closed court session held on July 24, 1917, remained undisclosed for a hundred years, until 2017. The verdict of that court was a death sentence.

Prison photographs of Mata Hari before her execution

How Did Mata Hari Die?

While in custody, her lawyer attempted to clear her of the charges. He unsuccessfully filed appeals and sent requests for clemency to the president. When all options were exhausted, the defense attorney suggested that the prisoner claim pregnancy (theoretically, this might have been possible). However, Margaretha rejected this proposal. Surviving prison photos of Mata Hari before her execution show a woman who held herself with dignity, as if she had already accepted that life no longer held meaning for her. When they came for her in the morning and ordered her to get dressed, the prisoner was outraged that she wouldn’t even be fed before her death. Breakfast was delivered to her cell at the same time as the coffin.

The execution took place on October 15, 1917. The shooting at the military range in Vincennes ended with a final shot to the head. Mata Hari’s body was handed over to the anatomical theater. Her embalmed head was kept in the Paris Museum of Anatomy, but it was discovered missing in 2000. The loss of the exhibit was attributed to the chaos of the museum’s relocation in 1954. According to documents from 1918, other parts of Mata Hari’s body were also in the museum’s possession, but the fate of her remains and their whereabouts remain unknown.

Afterword to a Life

Meanwhile, the personality of Margaretha Gertruida Zelle continues to intrigue historians. Some researchers believe that the motive behind her death sentence was the threat of exposing the spy’s connections with representatives of the French military and political elite. At the same time, experts consider the damage caused by Mata Hari’s subversive activities to be exaggerated: it is unlikely that the information obtained by the courtesan held significant value for either side. According to Colonel Orest Pinto of British and Dutch counterintelligence, “if the expansive courtesan had not gained the martyr’s halo from her execution, no one would have known her name.”

Ultimately, the name Mata Hari has become almost synonymous with the archetype of the femme fatale. For over a century, the embodiment of the fatal female spy has inspired writers (including a work about Mata Hari by Paulo Coelho) and filmmakers (among those who have created films about Mata Hari are Curtis Harrington, Nicholas Moore, Antonio Adamo, Quentin Tarantino, and others). The first film “Mata Hari” was made three years after her death, in 1920. After Asta Nielsen, Greta Garbo portrayed the legendary spy in a 1931 melodrama: the next film “Mata Hari” was a romanticized biography with a fictional interpretation of the facts of her life.

Greta Garbo as Mata Hari

Wars End with Peace

If one studies the material in books or films about Mata Hari, one will discover many alluring traits of the female image that illustrate the rationale behind intelligence agencies’ practice of recruiting “bed workers” (not just women). The 1967 parody film “Casino Royale” presents Mata Hari as the one true love of James Bond and the mother of his daughter, Matty Bond.

The story of the beautiful spy has even inspired erotic and pornographic films. In one such film – an erotic drama featuring the renowned actress in the titular role from the erotic bestseller “Emmanuelle,” Sylvia Kristel – the convoluted plot revolves around a love triangle between the heroine and two officer friends, a Frenchman and a German, who turn out to be adversaries during World War I. The creators of the film “Mata Hari” depicted the spy as a pawn, cynically sacrificed by the intelligence agencies that knew of her innocence. The film’s finale features a scene of reconciliation between former enemies after the war, as often happens in life, when wars, having buried innocent victims, end with peace.

Photos from open sources