Sometimes, history takes unexpected turns. We tend to think that mathematics began with numbers, counting, and the first inscriptions on clay tablets. However, new research on ancient from Mesopotamia, as reported by ZME SCIENCE, shows that people were thinking mathematically long before they learned to write numbers.

Sometimes, history takes unexpected turns. We tend to think that mathematics began with numbers, counting, and the first inscriptions on clay tablets. However, new research on ancient from Mesopotamia, as reported by ZME SCIENCE, shows that people were thinking mathematically long before they learned to write numbers.

It turns out that over eight thousand years ago, artisans were creating patterns based on clear principles. These were not just decorations; they were genuine visual formulas.

Halaf Culture Pottery: Patterns with Logic

This refers to the pottery of the Halaf culture, which existed approximately between 6200 and 5500 BCE in what is now the modern Middle East. Archaeologists have examined hundreds of fragments of clay artifacts from various settlements and noticed a common feature: the patterns on them had a clear, thoughtful structure.

Most often, the pottery depicted floral motifs—flowers, branches, leaves, and shrubs. But these images were not random or merely decorative. They adhered to symmetry, repetition, and specific numerical rhythms.

Interestingly, among the designs, there are almost no representations of . This suggests that the artists were not simply trying to showcase agriculture or daily life. Rather, the floral patterns likely held symbolic or aesthetic significance.

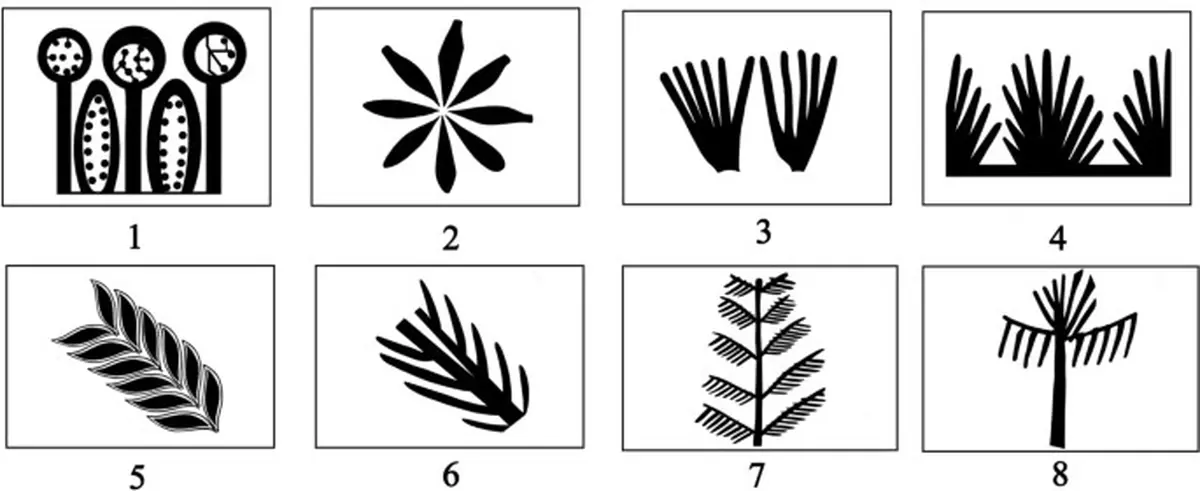

Four Categories of Floral Motifs: 1–2 Flowers, 3–4 Shrubs, 5–6 Branches, 7–8 Trees

Flowers That Follow Geometry

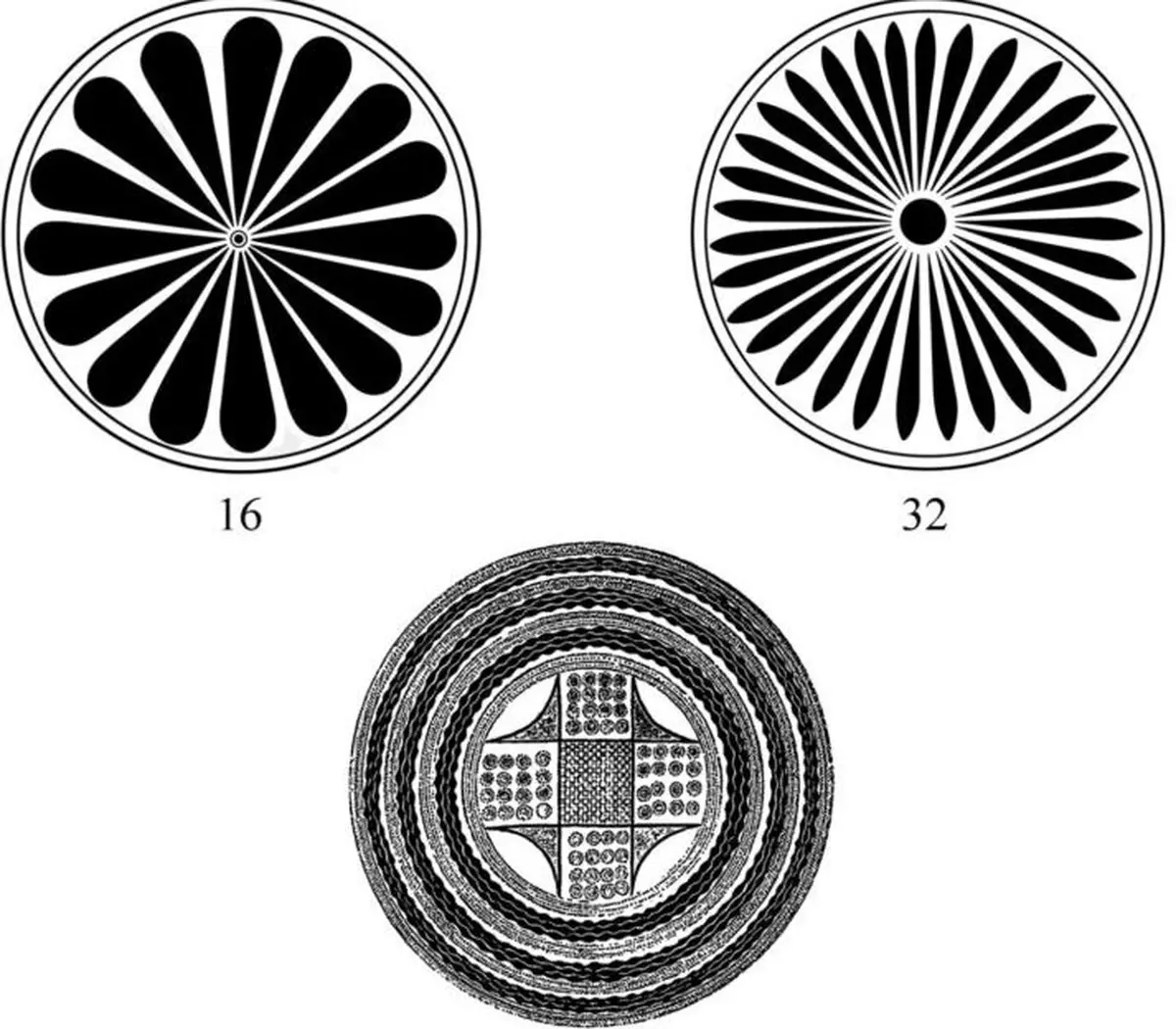

Researchers have been particularly intrigued by the floral patterns. In many cases, the flowers had a specific number of petals: 4, 8, 16, 32, or even 64.

These are not random numbers. All of them are powers of two—forming a geometric progression. This pattern indicates that the artisans had a solid understanding of the principles of dividing a circle, symmetry, and the repetition of elements.

At the same time, there were no recorded numbers or mathematical formulas at that time. People were thinking not in digits, but in shapes, rhythms, and visual patterns.

What Was the Purpose of Such “Mathematics”?

Researchers suggest that such principles could have been applied not only in art. This logic of division and symmetry could very well have been used in everyday life:

- during the distribution of harvest;

- in land division;

- in settlement planning;

- in crafts and construction.

Thus, the ornamentation on might not have been just decoration, but a reflection of the way an entire culture thought.

Mathematical Thinking Preceded Numbers

The first written numbers in Mesopotamia appeared around 3400 BCE. However, the patterns on Halaf pottery date back at least 3000 years earlier.

This means that mathematical ideas did not originate in the offices of scholars or with the advent of writing. They were born much earlier—in crafts, patterns, spatial distribution, and the daily lives of people.

In other words, there was first form, rhythm, and symmetry. Only later came numbers, formulas, and math textbooks.