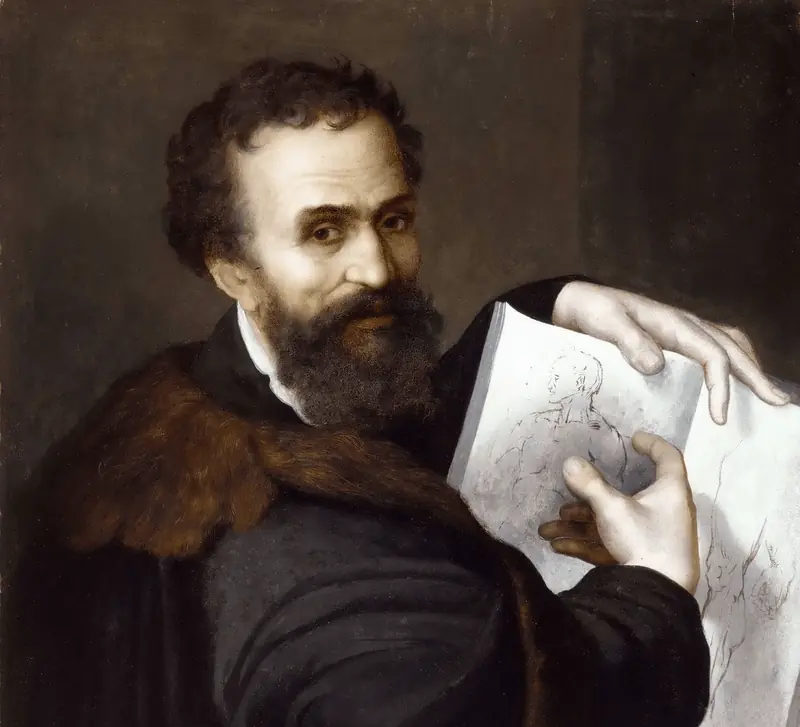

The biography of the remarkable sculptor, painter, architect, thinker, and poet was published during his lifetime—an unprecedented move in the realm of Western European art. Alongside his handcrafted masterpieces, documentary evidence of his 89-year earthly journey and unique creativity has been preserved: artistic sketches, contracts, contemporary reviews, and both professional and personal correspondence. Yet, despite the wealth of information available, even five centuries later, the titan of the High Renaissance, who lived from 1475 to 1564, remains an enigma to humanity.

The Phenomenon of Michelangelo

Debates continue not only about his immortal works but also about the personality of their creator. The artist, known for the most famous masterpieces on the planet, gained fame during his lifetime for the incredible realism with which he depicted the human body: beyond technical mastery, his genius reached spiritual heights in his art. Everything touched by his chisel, brush, or pen bears the imprint of the author’s thought and humanistic worldview. Goethe remarked on this artistic effect: “With his all-encompassing vision, Michelangelo surpassed nature itself.” The artist’s early biographers, colleagues, and students Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi noted that “the genius’s creativity was sent to Earth by the Almighty as a model of perfection in visual arts, and combined with a great poetic gift, he appeared to the world more as a celestial creator than a terrestrial one.”

A fragment of the fresco “The Flood,” located on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

The colossal power of his works indeed raises doubts about whether they could have been created by an ordinary mortal. It is hard to imagine that the multi-ton sculptures and gigantic frescoes were brought to life by a physically frail solitary creator suffering from hand arthritis and other ailments. A slave to his genius, he confessed in sonnets that his “body is made of rags,” and he even mentioned his ailments in the refined rhymes of his poetic verses. His deteriorating health and mental anguish became the price Michelangelo paid for his creative obsession. Despite earning a substantial income (from a young age, he received commissions for tomb decorations from members of the high nobility), the perfectionist and workaholic, who sought excellence in everything he undertook, was a proponent of solitude and asceticism. In his reflections, he stated that he “lived the life of a poor man: with minimal food, wine, and sleep.”

By Himself

Isolation and estrangement were necessary for the artist to concentrate his creative energy. This state connected him with Copernicus, Galileo, Kant, and Newton: a common root can be found in the inherent autism of geniuses (autos in Greek translates to “by oneself”).

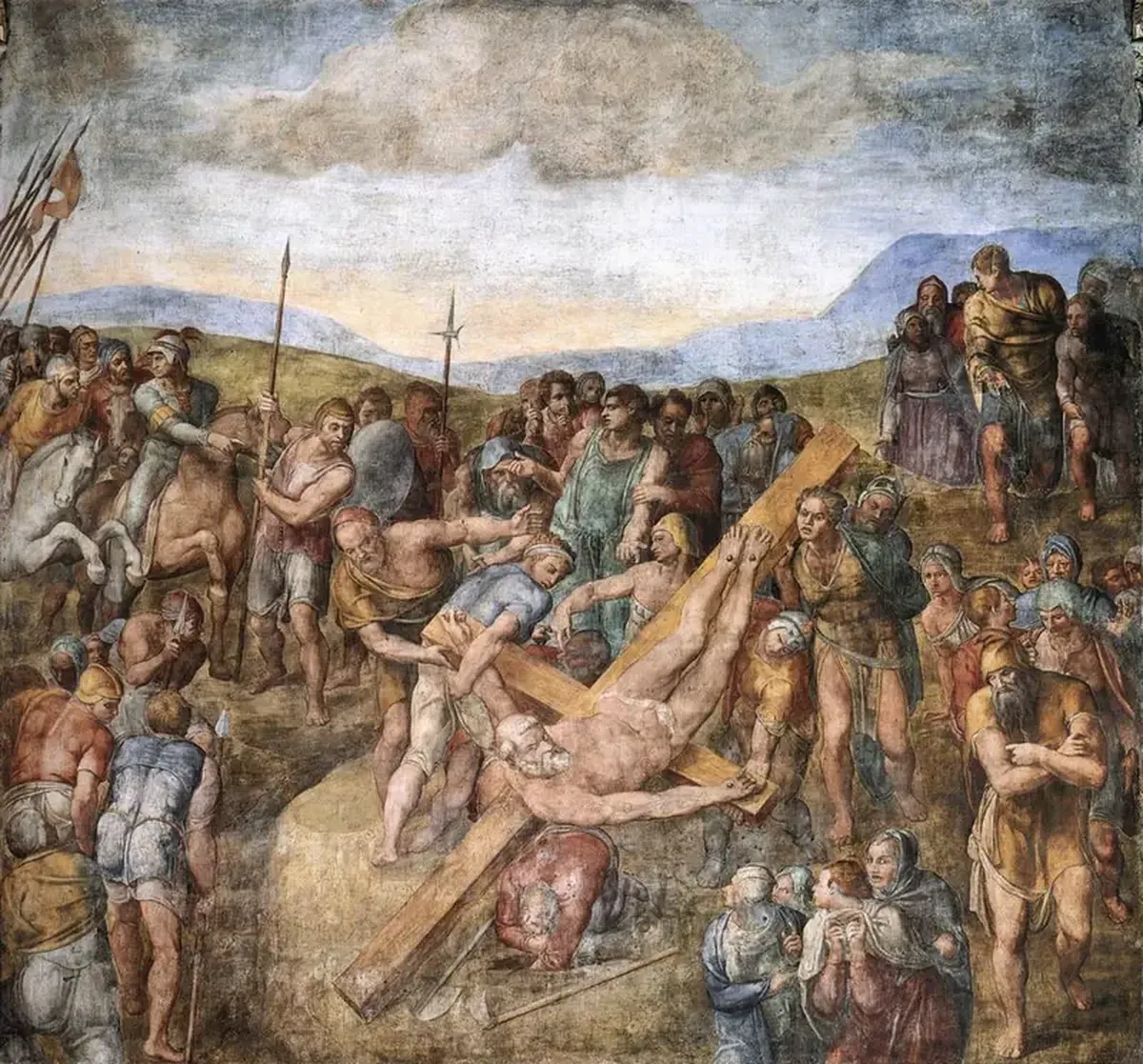

Due to his personal modesty, the master avoided official self-portraits, “hiding” them in external subjects. The most famous secret self-portrait is the face of Saint Bartholomew on the renowned fresco “The Last Judgment” (1541) in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo also placed himself among the crowd in “The Crucifixion of Saint Peter.”

“The Crucifixion of Saint Peter,” 1546-1550

Researchers believe that in the mysterious works of the giant sculptor and author of monumental frescoes, not only his self-portraits are “encoded” (for instance, in the sculptural composition “Florentine Pietà,” which the author envisioned as his personal tombstone, he “gifted” his face to the figure of Nicodemus), but also images of his lovers. Art historians have even discerned “hidden meanings” in biblical heroes in “The Meeting of Jesus Christ with Saint Veronica on the Way to Golgotha”: the painting in the altar of the Buonarroti family, next to the sculptor’s tomb complex created by his student and friend Giorgio Vasari, conceals two well-known figures. In one of the figures, we see Michelangelo (the artist was “unmasked” in the guise of the same biblical Nicodemus—characterized by his curly hair, distinctive beard shape, and broken nose), while in the neighboring figure is his fellow artist Giovanni de’ Jacopo (1494–1540), nicknamed Rosso Fiorentino. The close relationship between the master and the “Red Florentine” was also noted by the student in the biography of his teacher—the so-called “Lives.”

“Florentine Pietà,” 1547-1555

Only once was the imagined “woman-hater” spotted in friendly conversation with a member of the opposite sex: his poignant correspondence in verse with the famous poetess, Marchioness Vittoria Colonna, has been preserved. Most likely, these feelings were platonic. At that time, the author of the lyrical cycle was already 60, while his muse was 40. Having lived nearly 89 years, Michelangelo never established a family of his own. His brief will consisted of a single line of concise text: “The soul to God, the body to the earth, the property to relatives.”

A Blue-Blooded Stonecutter

Born in the Tuscan estate of Caprese, he hailed from a diminished noble family that traces its roots back to nearly imperial lineage. Despite the lack of documentary evidence confirming blood relations on his father’s side with Margravine Matilda of Canossa, Michelangelo himself had no doubts about his aristocratic heritage. Florentine annals mention his ancestors from the 13th century: they held municipal positions in their hometown. His grandfather, Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, for example, was a magistrate and had the honor of being included in the list of Buonomini: “the best names” referred to honorable citizens, and such laurels were bestowed upon only twelve Florentines. However, the hereditary financier had to make his mark in public service involuntarily, following the ruin of real estate dealings.

Sculpture by Cesare Zocchi. “Young Michelangelo Carving the Head of a Faun”

Michelangelo’s father, Lodovico Buonarroti, did not amass wealth: his modest income from the rural estate was hardly sufficient to support a large family, so he entrusted his second son to a wet nurse. The boy did not remember his biological mother: Francesca died during childbirth, giving birth to their fifth child. Michelangelo was six at the time, and out of pity, he was not informed of the loss. Growing up in a stonecutter’s family, he learned to carve hard stone and mold clay before he even mastered reading.

It was here that his difficult character formed, complicating his life with an inability to cooperate, submit, or compromise. His complex nature did not lend itself to friendliness, which prepared him for many problems with envious rivals and slanderers.

Angels and Demons

At the same time, Michelangelo himself earned the nickname Terribile. The man named after the archangel Michael was far from being an angel. His caustic nature manifested in witty jabs at his fellow craftsmen. During a quarrel in his youth while studying sculpture at the home of patron Lorenzo de’ Medici, a fellow student injured him, breaking his nose and distorting Buonarroti’s appearance with a crooked septum.

Michelangelo is attributed with aphoristic comments about the works of those he knew. Regarding the painting “The Mourning of Christ,” the wit remarked ironically that “the true mourning is the sight of all this.” And about another colleague, the critic sharply noted: “The best thing an artist can achieve is his own self-portrait” (the subject of the image was a bull).

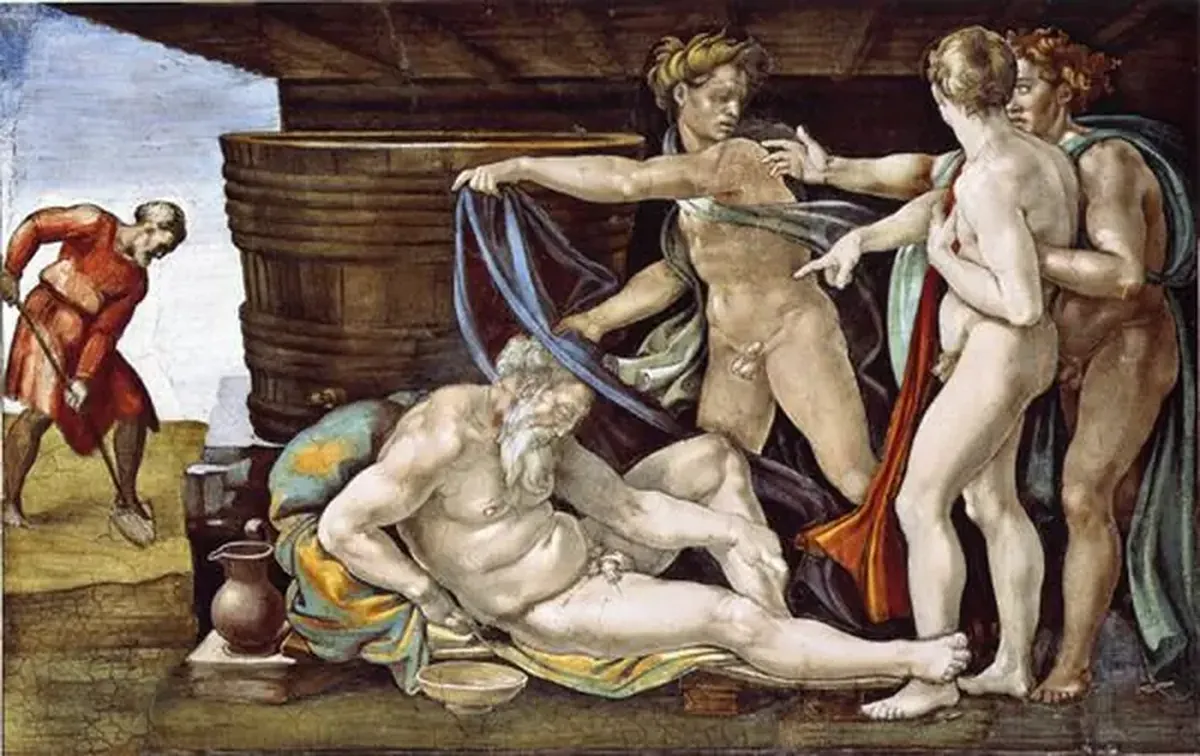

“The Drunkenness of Noah” — a fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508-1510

He made no exceptions even for his patrons. “It’s better to deal with the unclean forces than with this terrible man,” remarked Pope Leo X about working with Michelangelo. During the painting of the Sistine Chapel’s ceilings, the Pope reproached the artist for his sluggishness. When he once again came to assess the work and reminded him “under his breath” about deadlines, the enraged master, who did not allow viewers into the temple of art until the work was completed, rebelled, throwing paint-smeared brushes in the face of the high-ranking client. After the call to find another artist, the Pope “yielded” and patiently waited for the completion of the work “behind closed doors.” In the end, over four years (1508-1512), one of the “wonders of the world” was created: an incredibly complex work unmatched anywhere in the world.

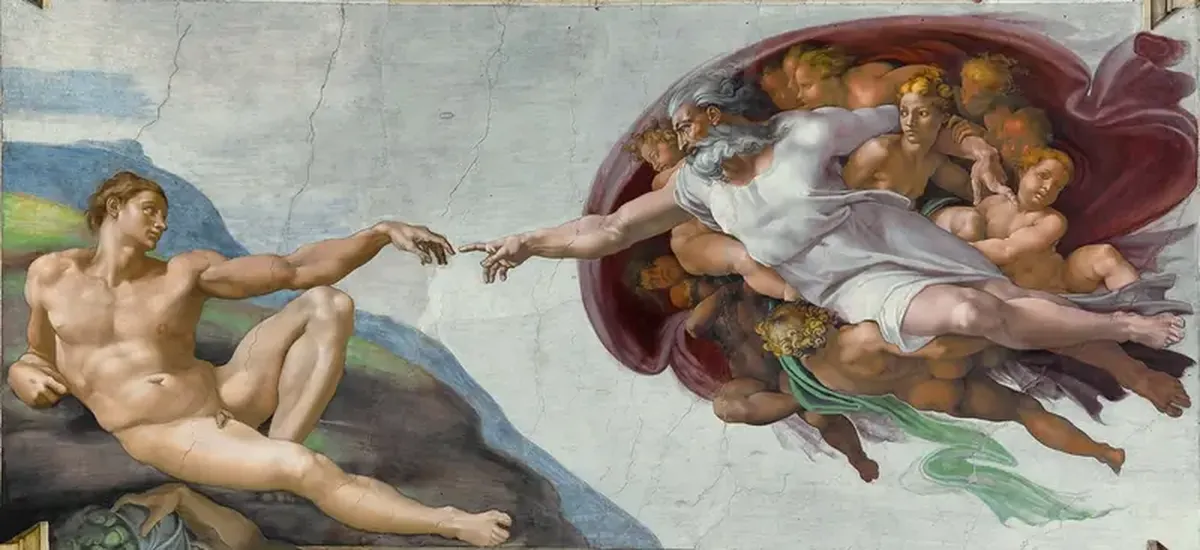

The ceiling fresco of the Sistine Chapel (circa 1508 – 1512)

Michelangelo’s Greatest Fresco

Michelangelo became the “decorator” of the Sistine Chapel not by his own choice. The fresco painting of the magnificent vault in Rome was commissioned by the warlike Pope Julius II, with whom Michelangelo had a complicated relationship. He had plenty of comparisons: the artist lived through thirteen popes and from 1505 worked on commissions for nine of them, starting with Julius II and ending with Pius IV. His work for the Vatican included tasks of varying scope and complexity—from designing papal furniture to the exhausting decoration of the ceiling space of the Sistine Chapel. Observing the grandeur of the latter, five million tourists each year cannot fathom how such an inspired work could have been executed reluctantly?!

The biblical story from the creation of the world to the flood involves over three hundred figures. Each fresco of the gigantic canvas is constructed from individual pieces, connected by the principle of the golden ratio. The idea of the painting was kept in the artist’s mind, without providing the client with any sketches for approval.

The most famous part of the “ceiling painting” of the Sistine Chapel became Michelangelo’s iconic work from 1511. The hands of God and man, nearly touching, have become the most reproduced religious painting of all time.

“The Creation of Adam,” 1511-1512

The Sistine fresco became the most perfect artistic confession in praise of humanity. Despite the grandeur of the composition featuring figures from Scripture, the energetic painting creates the impression of having been executed in one breath. Overwhelmed by the masterpiece, Goethe said: “One cannot conceive of the power of one man without seeing the Sistine Chapel.”

Did Michelangelo Undervalue Painting?

From 1537 to 1541, the master found himself once again on the scaffolding of the Sistine Chapel. He returned to the familiar walls after 25 years in the role of artist, sculptor, and architect of the Vatican Palace to fulfill the papal commission of Paul III—a grand fresco titled “The Last Judgment.” The reaction to this innovative “interpretation” of the Bible could have led to accusations of “immoral” authorship and heresy. The altar wall of the main abode of Christianity was filled with naked bodies with exposed genitals. The ambiguous fresco sparked a conflict over its indecent depiction with Cardinal Carrafa. Michelangelo was defended by the Pope himself. After the work was condemned by the Council of Trent, the author was obliged to cover the indecent parts in the painting.

“The Last Judgment,” 1537-1541

Michelangelo’s paintings are unique. The tondo (a circular image) of “Doni Madonna” in its original frame is considered the only surviving work of the artist in this genre (since 1635, the piece has been an exhibit in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence). The first known attempt at such an experience was the perfect adolescent work “The Torment of Saint Anthony.” The young author was only 12-13 years old at the time and began by copying a German engraving. In the workshop of his mentors, the Ghirlandaio brothers, the gifted student arrived in 1488 to learn the basics of painting and the main artistic means. Michelangelo studied drawing techniques from pencil copies for only a year, demonstrating sculptural vision of forms from his very first steps in painting. It is no coincidence that the young man soon transitioned to studying sculpture, which became his main calling.

“Doni Madonna,” circa 1504

It was sculpture that the artist referred to as “the light of painting,” emphasizing the difference between the closely related arts as between “the Sun and the Moon.” In an open dispute with Leonardo da Vinci, who equated painting with science, considering it the foundational basis of other arts, Michelangelo regarded this activity as a feminine pastime or child’s play. His true passion was sculpture, while architecture ranked second in his professional interests.

Sacred Sculptures of Michelangelo

The unparalleled king of the chisel and stone created 57 statues, of which 10 have not survived to this day. The artist adhered to the rule: “A good statue should not be damaged even by rolling down a hill.” When asked how he managed to convey the details of the human body so accurately in solid rock, Michelangelo replied that he simply cuts away everything unnecessary from the marble block.

“Bacchus,” 1497

In fact, his best sculptures—“David,” “Pietà,” and “Bacchus”—were created based on early anatomical studies. With the permission of the abbot of the Santo Spirito monastery in the 1490s, the sculptor studied the structure of the human body in the local morgue. In gratitude for this opportunity, the sculptor gifted the local church a crucifix he carved with anatomical precision.

At the beginning of his career, Michelangelo was even accused of fraud: he executed the statue of “Cupid” in the ancient Greek style so perfectly that the client resold it at an exorbitant price as an antiquity unearthed from the ground. After the revelation, the money was returned to the deceived buyer, but the Roman cardinal did not want to part with the wonderful master: inviting Michelangelo for an introduction, he kept him in the Eternal City for work.

“Madonna at the Steps” (1490-1492)

In the artist’s early reliefs, “The Battle of the Centaurs” and “Madonna at the Steps” (1490-1492), characteristic features of the sculptor’s creative style emerged: monumentality, plastic expressiveness, dramatic character of the images, and reverence for the perfection of the divine creation—humanity.

The marble double sculpture “Pietà” for St. Peter’s Cathedral in the Vatican was executed by the master at the age of 24. This was the only instance in his practice where he placed his own name on the work.

“Pietà” or “The Mourning of Christ,” 1498-1499

The most famous five-meter sculpture “David” was created by the author over three years. Typically demanding of his materials, the master at that time inexplicably agreed to work with a discarded block of marble with traces of the chisels of two predecessors who had abandoned the work due to the unsuitability of the material. Despite the poor quality of the material, with voids and cracks, the genius carved from it his most brilliant masterpiece, which biographer Giorgio Vasari said “took glory from all the statues that existed before.”

“David,” 1501-1504

Talent Saved His Life

When in 1527, Michelangelo’s native Florence replaced the exiled rulers from the Medici family with a republican government, the “court” artist, who worked for Pope Clement VII, supported the republicans and was appointed head of the defensive fortifications. The fruits of the architect’s labor prevented the papal forces from reclaiming the city, and Florence faced a ten-month siege by imperial troops. When Michelangelo found himself in captivity, he had to prove that he was not a spy but an artist. His artistic talent helped him avoid inevitable punishment. When, blindfolded, Michelangelo simultaneously drew two flawless one-meter circles with both hands, the head of the city’s defense appointed the skilled artist as the architect of the fortification bastions. After the former authority returned, Michelangelo could have been executed as a traitor, but Clement VII forgave him, hiring him back into service.

Among the architect’s achievements are the work on the Medici Chapel complex in Florence, the design of the Capitol Square ensemble, the construction of the stairs of the Laurentian Library, and the development of the dome of St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome. Michelangelo worked on the latter task until his death, engaging in the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. The position of chief architect of the Catholic sanctuary prompted Michelangelo to a noble gesture: he announced his willingness to oversee the construction of the basilica free of charge, out of love for God…