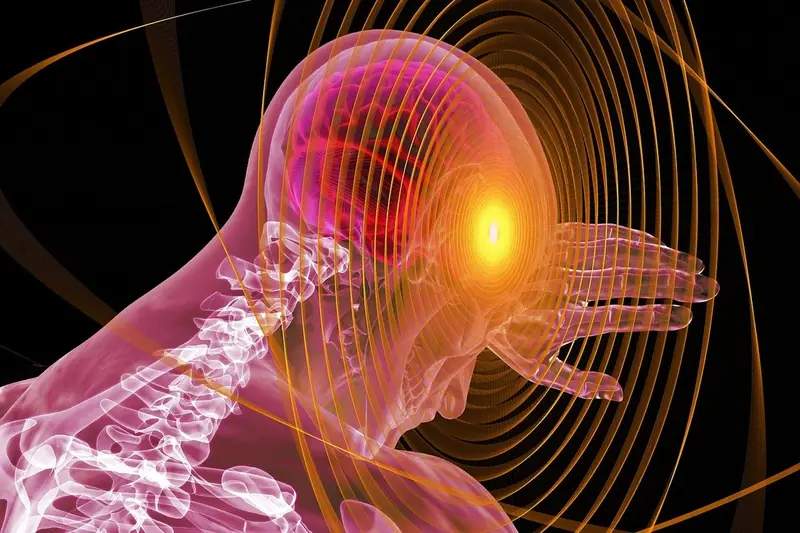

A team of neurobiologists from the University of Pennsylvania has uncovered what sets cold-blooded psychopaths apart from ordinary individuals. The differences lie within the human brain.

In a recent study, researchers identified tiny yet significant features in the brain’s structure that may explain why psychopaths think, feel, and behave so differently from the rest of us.

What Did the Researchers Discover?

Using MRI scans, the team compared the brains of 39 adult men with high levels of psychopathy to those of men without any signs of the condition (the control group). What they found was astonishing.

In the brains of psychopaths, researchers discovered wrinkled areas in the so-called basal ganglia, which control movement and learning, the thalamus, which acts as a relay station for sensory information, and the cerebellum, which helps coordinate motor functions.

However, the most striking changes were found in the orbitofrontal cortex and insular regions, which are responsible for emotional regulation, impulse control, and social behavior. In other words, the parts of the brain that typically prevent most people from lying, attacking, or harming others were significantly impaired in psychopaths.

The scans also revealed weakened connections between brain areas associated with empathy, guilt, and moral reasoning in these participants. This suggests that the heartless behavior of psychopaths is not merely a personality issue but has deep roots in their neural connections.

And That’s Not All

The study, published in the European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, also found notable disruptions in the amygdala. This powerful brain region controls fear, anger, and emotional recognition, which are fundamental to functioning in a social environment.

When this system malfunctions, the result is not just mood swings but a complete breakdown in how a person understands others and regulates their behavior. This dysfunction can manifest in rather eerie ways: psychopaths often struggle to express emotions through facial expressions, making them appear cold and detached.

Thus, the differences in brain structure point to a biological basis for why psychopaths behave the way they do, as reported by the Daily Mail.

According to the scientists, these findings will help them develop new methods for identifying and treating individuals prone to extreme antisocial behavior.

The neurological differences identified by the researchers explain why less than one percent of the world’s population are psychopaths. Interestingly, 20 percent of people in prisons exhibit psychopathic tendencies.

According to the study, most individuals with such tendencies do not commit violent crimes, but 60 percent of them lie in casual conversations, 40-60% ignore speed limits on the roads, and 10% use illegal drugs.

Previous studies have even suggested that psychopaths may have impaired functioning of the mirror neuron system—a part of the brain that helps us imitate and learn behavior by observing others. In other words, while most people instinctively learn compassion by watching someone cry or suffer, a psychopath may feel nothing at all.

Many diagnosed psychopaths do not end up in prison or treatment. They integrate into society, learning to mimic normal emotions, mask dangerous impulses, and remain unnoticed.