A connoisseur of beauty and paradoxes urged us not to destroy legends: they reveal the true essence of humanity. Here’s a biography and intriguing facts about the life of the Irish poet, writer, essayist, playwright, journalist, wit, dandy, and a key figure in European modernism, whose life was both brilliant and tragic.

Bohemian Atmosphere

Oscar Wilde was born on October 16, 1854, in Dublin, Ireland. He had Dutch roots on his father’s side and Italian on his mother’s. One branch of his family settled in Ireland in the late 17th century, while the other arrived a century later. Before marrying Oscar’s mother, Sir William Wilde had three illegitimate children whom he educated but did not raise. In his marriage to Jane Wilde, three more children were born, but the youngest girl died at the age of ten from meningitis, a fate that would ultimately claim Oscar Wilde as well. The future writer was two years younger than his brother. The sons of a prosperous doctor and philanthropist were born with a “silver spoon in their mouths.” They not only lacked for nothing but also had the best opportunities for development.

William Wilde, Oscar’s father, was even knighted: he served as a medical advisor and assistant to the Commissioner of the Irish Census. A leading otolaryngologist, he not only treated the eyes and ears of wealthy patients but also provided charitable care to the city’s poor at his own dispensary on the grounds of Trinity College in Dublin. Meanwhile, the head of the family also found time to research peasant folklore and Irish archaeology. His wife, Jane Wilde, was equally accomplished. She raised their three children in an atmosphere filled with poetic evenings attended by numerous gifted individuals and European celebrities. Mrs. Wilde herself was part of this creative circle: an Irish nationalist, she wrote revolutionary poetry under the pseudonym Speranza (Italian for “Hope”).

From birth, the children were immersed in literature, poetic imagery, and beauty in all its forms. Their home was filled with neoclassical busts and paintings that shaped Oscar’s perception of the beautiful. The high aesthetic standards were embraced by a person who grew up surrounded by Hellenistic art, forming a natural atmosphere of existence. In the summers until he turned 20, Oscar would travel to his father’s country villa, where his playmate was the future writer George Moore.

Little Oscar in a dress

The Sacred Text of Beauty

A French governess taught Wilde French, while a German tutor taught him German. Lively, sociable, and ironic, Oscar had a knack for reading from an early age and gave the impression of someone for whom learning came easily. He graduated from Portora Royal School with a gold medal and a prize for his success in studying the Greek text of the New Testament. Next came a Royal School scholarship to the legendary Trinity College in Dublin, whose illustrious alumni included Lord Byron and Isaac Newton: within those walls, it was easy to feel chosen!

In lectures on ancient history and culture, Wilde once again showcased his brilliant aptitude for studying ancient languages. Alongside this knowledge, he was introduced to lectures on aesthetics that transformed his consciousness. It was during this period that the young man solidified his Hellenistic preferences and sympathies for the Pre-Raphaelites. He entered the classical department of Oxford University as an aesthetic, dandy, and philosopher. His talent was recognized by all his professors. At Oxford, he was awarded the prestigious Newdigate Prize for his poem “Ravenna.”

Oscar quickly identified his role models. He drew his personal philosophy of art (aestheticism) from the “sacred text of beauty” – the works of Renaissance historian John Ruskin and his university disciple Walter Pater. Both professors influenced Victorian English culture. While the patriarch praised beauty in conjunction with goodness, his disciple did not shy away from beauty mixed with evil. The student found both concepts intriguing.

Visits to Italy and Greece during his studies at Oxford exposed him to artistic layers he had never considered before. Along with his Irish accent, Wilde left behind his former beliefs at Oxford: with eloquence and impeccable English pronunciation came a disdain for conventions and a disregard for taboos. As he had dreamed, Oscar earned a reputation as a brilliant individual whose life was easy and vibrant.

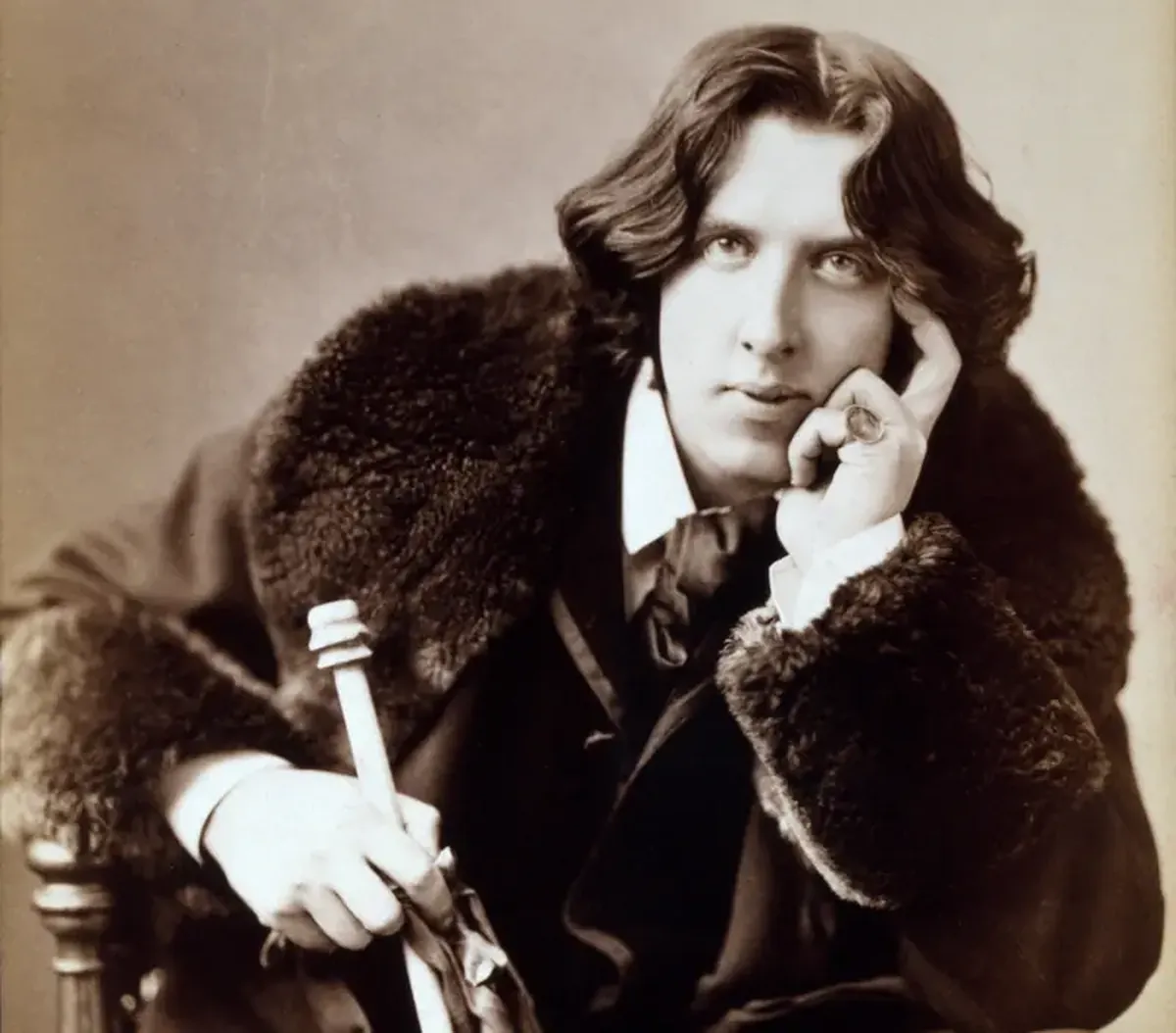

Oscar Wilde, London, 1881

The Star Attraction

After university, Oscar Wilde moved to London. By 1878, the trendsetter of British fashion was already recognizable on the streets of the capital. It was hard not to notice the tall (6’3″) young man in a short velvet jacket trimmed with braid, a thin silk shirt with a wide collar, a soft green tie, knee-length satin trousers, black stockings, patent leather shoes, a voluminous cloak, and a picturesque cap. Moreover, he wore a green carnation in his lapel and held a lily or sunflower in his hand. These flowers were considered the pinnacle of perfection by the Pre-Raphaelite artists, who represented a movement that opposed academic traditions in English painting and poetry at the end of the 19th century.

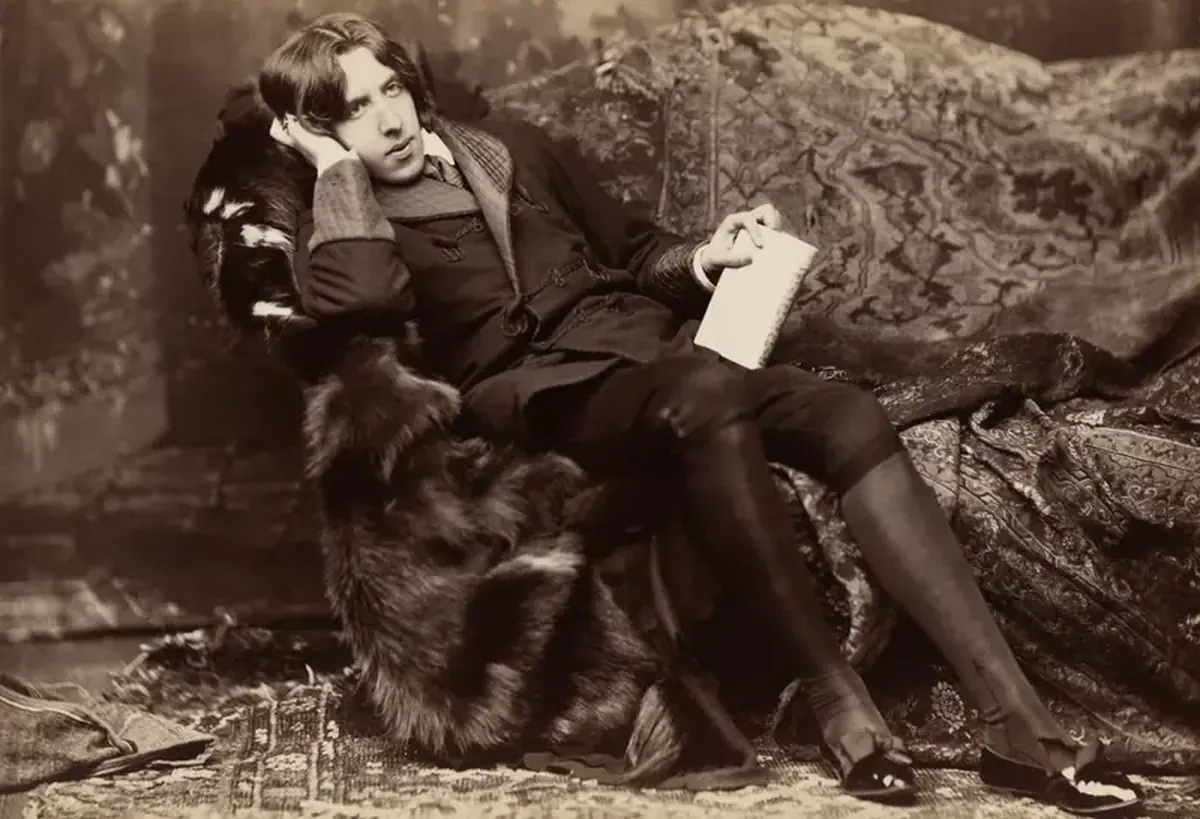

Oscar Wilde, 1882

However, when students from Harvard University attended his lecture in such attire, Wilde humorously remarked, “For the first time, I ask God to rid me of followers.” It was no wonder he was called the “Irish wit”: self-irony always saved the writer when his outrageous antics were misunderstood. Wilde’s “artistic” image and affected behavior often became the target of caricaturists, yet this self-expression made him popular in social circles. Wit and the ability to attract attention were undeniable talents of Oscar, who was eagerly invited to salons to entertain guests. The “star attraction” not only joked and bantered but also delighted the audience with incredibly “picturesque” impressionistic poems.

In 1882, he sailed from London to New York and made local reporters smile with his “press confession”: “Ladies and gentlemen, I am disappointed with the ocean – I expected more from it.” At customs, the poet amused those present with his response to a declaration inquiry: “I have nothing to declare but my own genius.” While American lecture audiences were captivated by Wilde, admiring the exquisite beauty of his speech, detractors criticized his inappropriate self-promotion. But Wilde wouldn’t be himself if he didn’t boast to a friend in a letter from another continent: “I have already civilized America – only the sky remains to conquer.”

Postcard commemorating Oscar Wilde’s visit to San Francisco, 1882

The Game of Wit

After spending a year in America, Wilde made a name for himself in Paris, where he easily won the affection of Paul Verlaine, Émile Zola, Victor Hugo, and Anatole France.

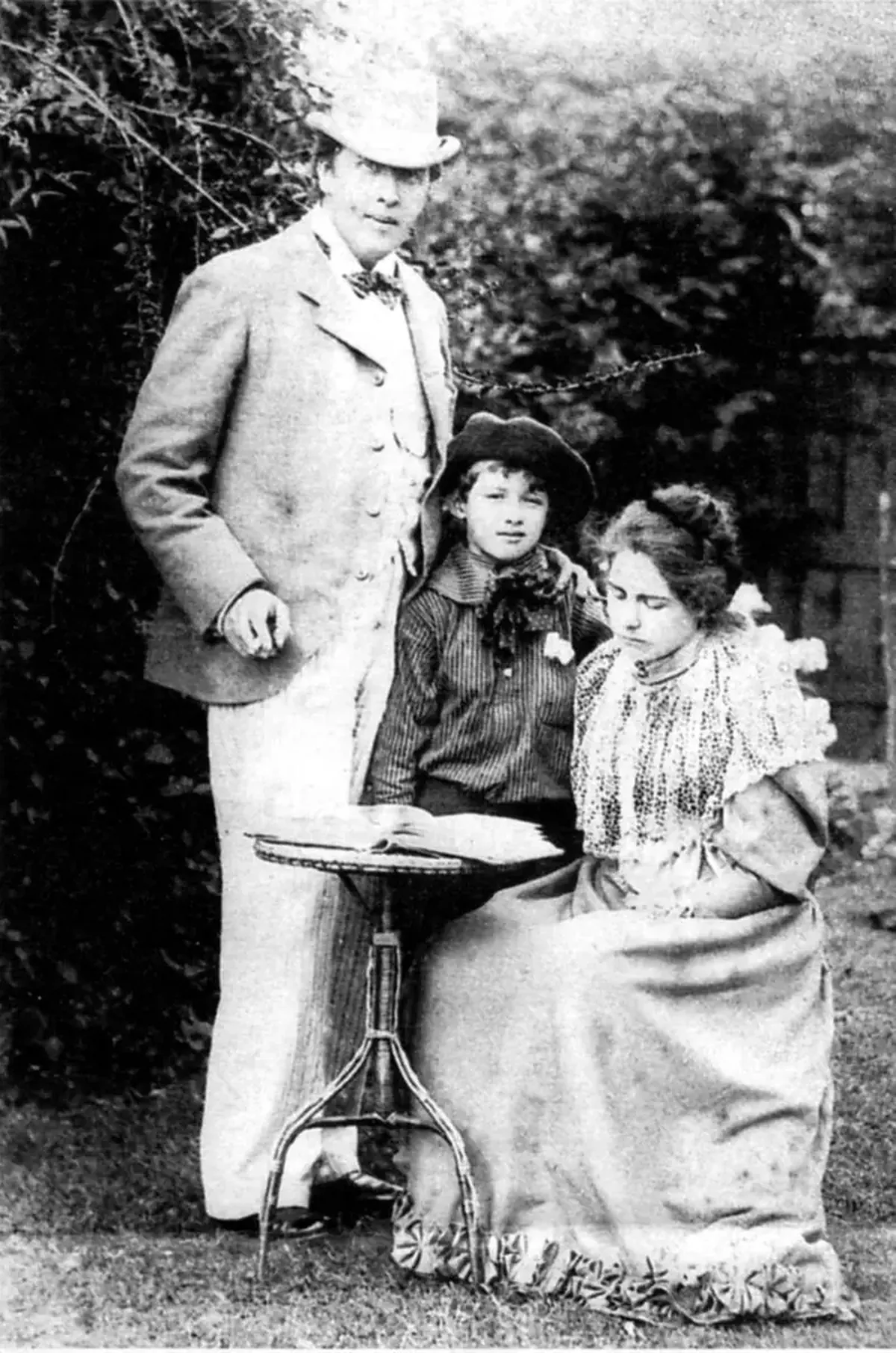

In 1884, Wilde met Constance Lloyd, who became his wife and the mother of his two sons: Cyril was born in 1885, and Vivian in 1886. Oscar wrote stories for his children, which filled two collections.

Oscar Wilde with his wife Constance Lloyd and son Cyril

Feeling a sense of responsibility towards his family, the young father took on the role of editor for the magazine “Woman’s World”: his sociability and connections proved useful in journalism and fundraising for the publication. Although Bernard Shaw acknowledged his editorial successes, Wilde quickly lost interest in this endeavor. He focused on literary creation.

Wilde may seem to many like a sybarite capable of writing only one novel, and even that one is considered immoral. In response to accusations of immorality, the author claimed that art does not depend on morality, while critics found a moral lesson in the novel: one cannot kill one’s conscience without consequence. Besides “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” the writer produced many successful plays, comedies, poems, essays, short stories, and theoretical studies (his work “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” is particularly interesting: this philosophical piece rejects marriage, family, and private property).

In 1892, after the premiere of the comedy “Lady Windermere’s Fan,” Wilde continued the performance with his own appearance before the audience: he came out for a bow… with a cigarette in hand. “Ladies and gentlemen,” addressed the “apostle of beauty” to the audience, “do not consider it rude that I am smoking before you: it is equally impolite on your part to distract me from my occupation.”

After “An Ideal Husband” and “The Importance of Being Earnest,” newspapers hailed Wilde as “the best contemporary playwright.” The only criticism was that his overly whimsical wit sometimes captivated Wilde to the point of becoming an end in itself.

A unique work in the writer’s oeuvre is the one-act play “Salomé,” written specifically for Sarah Bernhardt. Unfortunately, in Great Britain, the censorship banned the production due to its biblical subject matter. This was not the only restriction that marred Wilde’s life and that of his family.

“Love That Hides Its Name”

Oscar Wilde attempted to joke even during the humiliating trial for charges of sodomy. This flaw in noble circles was not his alone, but his circumstances led to the scandal. Oscar had the misfortune to ignore the threats from the father of his lover, who demanded that he end his disgraceful relationship with his son. The son of the Marquis of Queensberry, Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed Bosie, was 16 years younger than Wilde, yet he sought the acquaintance of a wealthy patron. Wilde was known for his lavish gestures and never denied his young lover, who had left Oxford University and was unwilling to hide his dubious connections, thus providing grounds for blackmail.

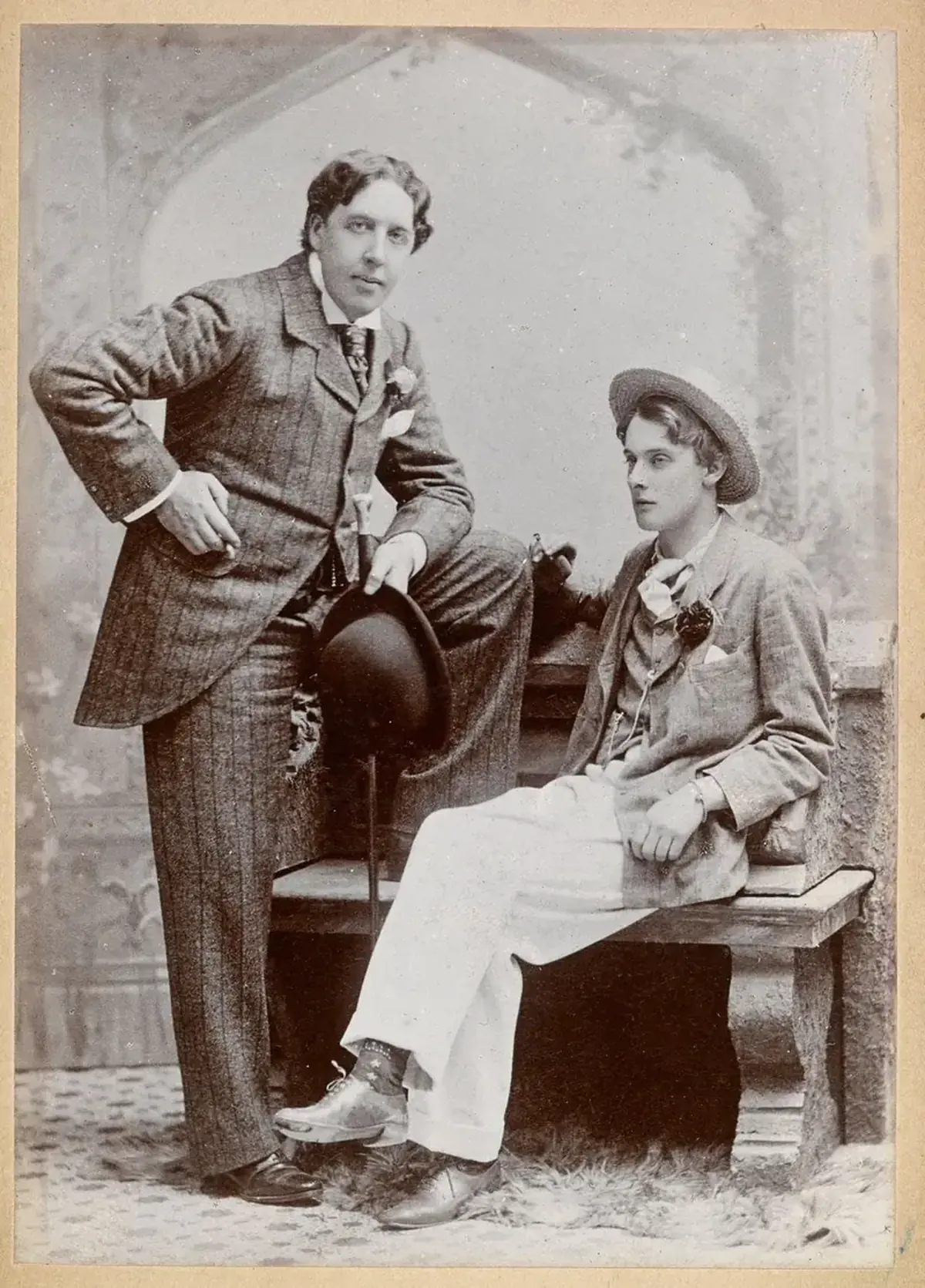

Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas

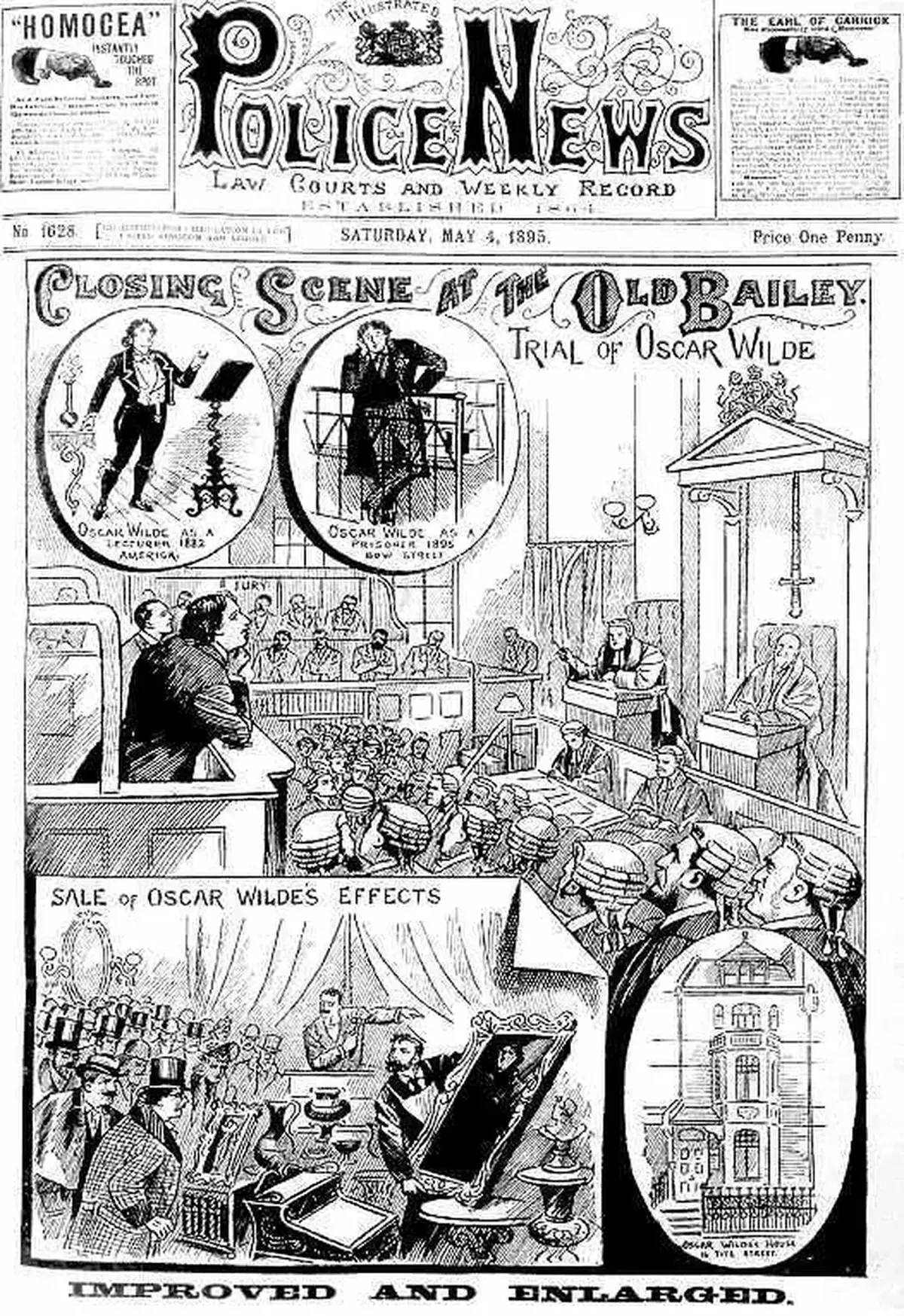

The writer’s mistake was to sue Bosie’s father for libel when he accused him of “practicing sodomy.” The Marquis did not even accuse Wilde, and the insult could have been left unanswered. However, Oscar, as always, became too carried away, and now Queensberry had to prove in court that he was not slandering Wilde. Ultimately, the libel case was dropped, and Wilde was immediately charged with violating public morality. The prosecutor passionately explored the “aspects of homosexuality” using examples from the literary works of the author of “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” and received a brutally frank manifesto in response to the question about the meaning of the line “Love That Hides Its Name.” This inappropriate eloquence cost the writer two years in prison for “gross indecency” and led to the collapse of his family.

Oscar Wilde on trial, illustration from The Illustrated Police News, May 4, 1895

“The Drama of the Final Act”

Neither Douglas nor other libertines involved in the case were held accountable. Instead, Wilde lost everything. The two prisons broke him. Malnutrition and harsh conditions undermined the health of the still young writer. One of the falls resulted in a perforated eardrum, which later led to illness and Oscar’s death. The meaning of these trials turned out to be the subsequent reform of the treatment of British prisoners: it was revised after the publication under a pseudonym of the book “The Ballad of Reading Gaol.”

Wilde’s friends turned away from him, and Alfred Douglas never visited the man who had once lived beautifully at his expense (he immediately went abroad, where he sold and pawned expensive gifts and letters from his lover). Moreover, at one point, the young man who had shattered Oscar’s life “finished off” the prisoner with a reproachful letter: “When you are not on a pedestal, no one cares about you.”

Only his unfortunate wife visited Wilde in prison twice: first, she informed the wrongdoer of the death of his beloved mother, and later brought papers for him to sign, entrusting her with the care of their children. After that, Constance changed her and her sons’ last name and never showed the children to their father again. She continued to send her husband money even after his release but refused to meet with him.

Upon his release, Wilde moved to France and similarly changed his name, becoming Sebastian Melmoth. He borrowed the new surname from the novel of his great-uncle “Melmoth the Wanderer.” Oscar hid from acquaintances, moving from place to place and feeling like the same wanderer as that literary hero. Bernard Shaw described this period of his friend’s life: “Wilde greatly simplified his life so that nothing would hinder him from feeling the drama of the final act.” Before his death, the writer remarked that he would not survive the 19th century: “My compatriots will not tolerate my continued presence.”

Oscar Wilde’s grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery

Oscar Wilde left this world after a painful eight-hour agony on November 30, 1900. The cause of his premature death was acute meningitis due to an ear infection. The writer died in exile at the age of 46. His grandson, who holds the rights to the creative legacy of his illustrious grandfather, considers his family a victim of homophobia.