For nearly three centuries, the portrait of a modest girl with a tray has accumulated so many legends, rumors, and conflicting versions that untangling the truth from fiction is nearly impossible. Is it a story of love or cold calculation? A chance encounter or a carefully crafted plan? Or perhaps there was no story at all, and the artist simply saw a beautiful girl? There are so many versions that they could fill a television series.

For nearly three centuries, the portrait of a modest girl with a tray has accumulated so many legends, rumors, and conflicting versions that untangling the truth from fiction is nearly impossible. Is it a story of love or cold calculation? A chance encounter or a carefully crafted plan? Or perhaps there was no story at all, and the artist simply saw a beautiful girl? There are so many versions that they could fill a television series.

Moreover, this painting survived a world war, became one of the first advertising faces in marketing history, and remains the most replicated image for almost three hundred years. Thus, the story of the “Chocolate Girl” resembles a detective tale more than an art critique.

Version #1: Cinderella from a Viennese Café

According to the most romantic version, the painting “Chocolate Girl” depicts Anna Baltauf – a girl from a noble but impoverished aristocratic family. In 1745, she worked in a Viennese café, serving the fashionable drink of the era – hot chocolate, which had just appeared in Europe and was considered a true luxury.

One day, Prince Dietrichstein, a descendant of one of the wealthiest and most influential Austrian families, entered the café. Upon seeing the modest yet graceful girl with impeccable posture, elegant movements, fair skin with a healthy blush, and small feet (which hinted at her noble origins), he fell in love at first sight.

And here begins the real scandal. Despite the furious protests from his family and the shock of high society, the prince married Anna. Before the wedding, he commissioned a portrait of his beloved from the fashionable Swiss artist Liotard, asking him to depict her exactly as he first saw her: in the attire of a humble waitress. It’s reminiscent of a true Cinderella story, only instead of a glass slipper, there’s a cup of chocolate.

Version #2: The Clever Title Hunter

But there’s an entirely different legend. According to this version, the reality was much more prosaic and cynical.

The girl, whose name was not Anna but Charlotte Baltauf, did not come from an aristocratic family but from a regular servant family. Her mother prepared her daughter from childhood for the only possible career for a poor beauty – to become the mistress of a wealthy man. There were no other paths to a good life for girls like them.

Legend has it that Charlotte first saw the prince not in the café but in the house of an aristocrat where she worked. The clever and determined girl began to systematically catch his eye, drawing attention, and demonstrating modesty and politeness. The plan worked – soon she became the prince’s mistress.

But Charlotte was not content to be just one of many. She managed to have the prince introduce her to his guests, stop seeing other women, and – most importantly – marry her, causing a true scandal in high society.

When the prince commissioned a portrait of his fiancée from Liotard and told him about his future wife, the artist grimly remarked, “Such women always get what they want. And when they do, you’ll have nowhere to run.”

Did the prophecy come true? To some extent, yes. The prince lived with Charlotte his entire life, kept other women at bay, and died leaving her all his possessions. In her later years, she achieved recognition and respect in the world. So, she truly got everything she wanted.

Version #3: The Empress’s Maid

There’s yet another version – the artist did not receive a commission but wanted to paint a portrait of a beautiful girl who captivated him with her beauty. This girl was a maid of the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa named Baldauf, who later became the wife of Joseph Wenzel of Liechtenstein.

Which of these stories is true? No one knows for sure. The identity of the model remains officially unconfirmed. However, art historians agree on one thing: all three versions are valid, as none have been conclusively disproven by documents.

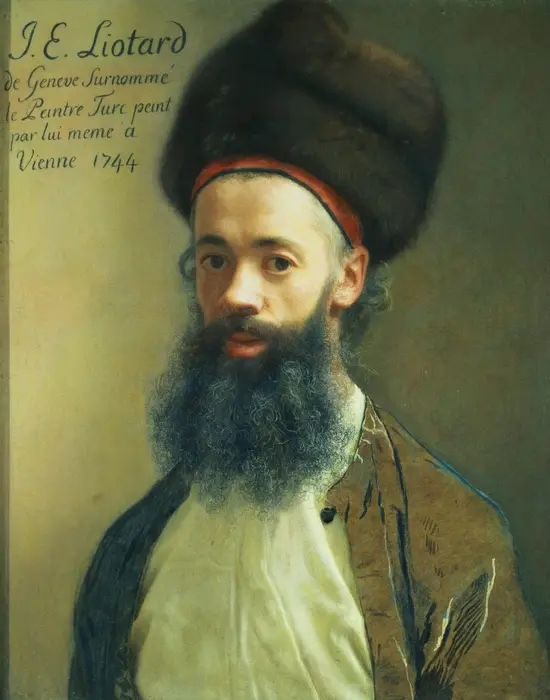

The Traveling Artist in Turkish Garb

What do we know about the master who created this masterpiece? Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702-1789) was an 18th-century Swiss artist born in Geneva. He was a true cosmopolitan of his time: traveling throughout Europe, living in Constantinople, where he adopted the habit of wearing Eastern clothing and grew a long beard – at a time when this caused quite a stir in society. For this, he was often referred to as the “Turkish artist.”

Jean-Étienne Liotard. Self-Portrait

Liotard worked at royal courts, painting portraits of monarchs and aristocrats. His signature technique was pastel on parchment – a complex material that required virtuoso skill. This pastel technique allowed him to capture the finest details, making the painting appear lifelike.

He created “Chocolate Girl” sometime between 1743 and 1745 (the exact year is not established, but most researchers lean towards 1745). Understanding that his work would not be properly appreciated in Vienna, where he was at the time, he took it to Venice. There, the painting was purchased by Count Francesco Algarotti, who was collecting works for King Augustus III of Saxony.

Algarotti was thrilled. In a letter, he wrote: “I bought a pastel by the famous Liotard. It is executed in subtle gradations of light and with wonderful relief. The nature depicted is in no way altered… This is Holbein in pastels.”

The painting was bought for 120 gold ducats – nearly 500 grams of gold, which in today’s equivalent is about $30,000. Not a bad price, especially for the 18th century.

Enchanting Details

What is so special about this portrait of a servant girl with chocolate? At first glance, she appears to be an ordinary girl with a tray. No dramatic plots, no lavish decorations. But it is precisely in this simplicity that Liotard’s genius lies.

The girl stands in a modest yet neat outfit: a golden-ochre bodice with a peplum, a gray skirt, a crisp white starched apron, and a silky pink cap with lace. The colors are chosen to create a sense of freshness, comfort, and tranquility.

Her face is delicate, slightly melancholic, with a light blush. Her eyes are cast downward – a sign of modesty and humility. Yet her well-groomed hands, impeccable posture, and small foot reveal her noble origins.

And what detail! Liotard captured the very moment – in every wrinkle of the apron, in the reflections of the glass. The folds of the clothing are rendered so precisely that it seems that in another moment, you could hear the rustle of the fabric, the click of heels on the floor. The cup made of Meissen porcelain (by the way, this is the first depiction of Meissen porcelain in European art – its production began in Europe shortly before the painting was created) shines as if it were real.

But what impresses the most is the glass of water. It is so transparent and realistic, with all its reflections, light refractions, and reflections, that you want to reach out and take it. It’s a true masterpiece within a masterpiece!

By the way, an interesting detail: the cup sits on a special saucer called a tremblez (from French “trembleuse” – “trembling hands”). It was invented in the 17th century specifically for hot chocolate – the drink was very expensive, and to avoid spilling a single drop of the precious liquid, a saucer with a deep indentation in the center was created to securely hold the bottom of the cup. Such dishes are rarely seen today, but they were quite common in the 18th century.

Tremblez

Adventures During World War II

Since 1765, the painting “Chocolate Girl” was safely housed in the Dresden Gallery of Old Masters. However, with the onset of World War II, the fate of the painting was in jeopardy.

The Nazis transported it along with other priceless artifacts to Königstein Castle above the Elbe – a fortress on a high cliff that seemed the safest place. There, the paintings were stored in damp, cold cellars amid the chaos of war.

How a pastel on parchment – an extremely fragile and delicate material – survived such horrific conditions remains a mystery. Art historians are still astonished: not a single crack, not a single damage. It’s a miracle!

After the war, the collection was discovered by Soviet troops, and the famous canvas returned to Dresden, where it remains to this day. Museum visitors say that the painting by the Swiss master literally draws you in like a magnet – you can stand before it for hours, as if time has stopped along with the girl on the threshold.

The First Brand in Marketing History

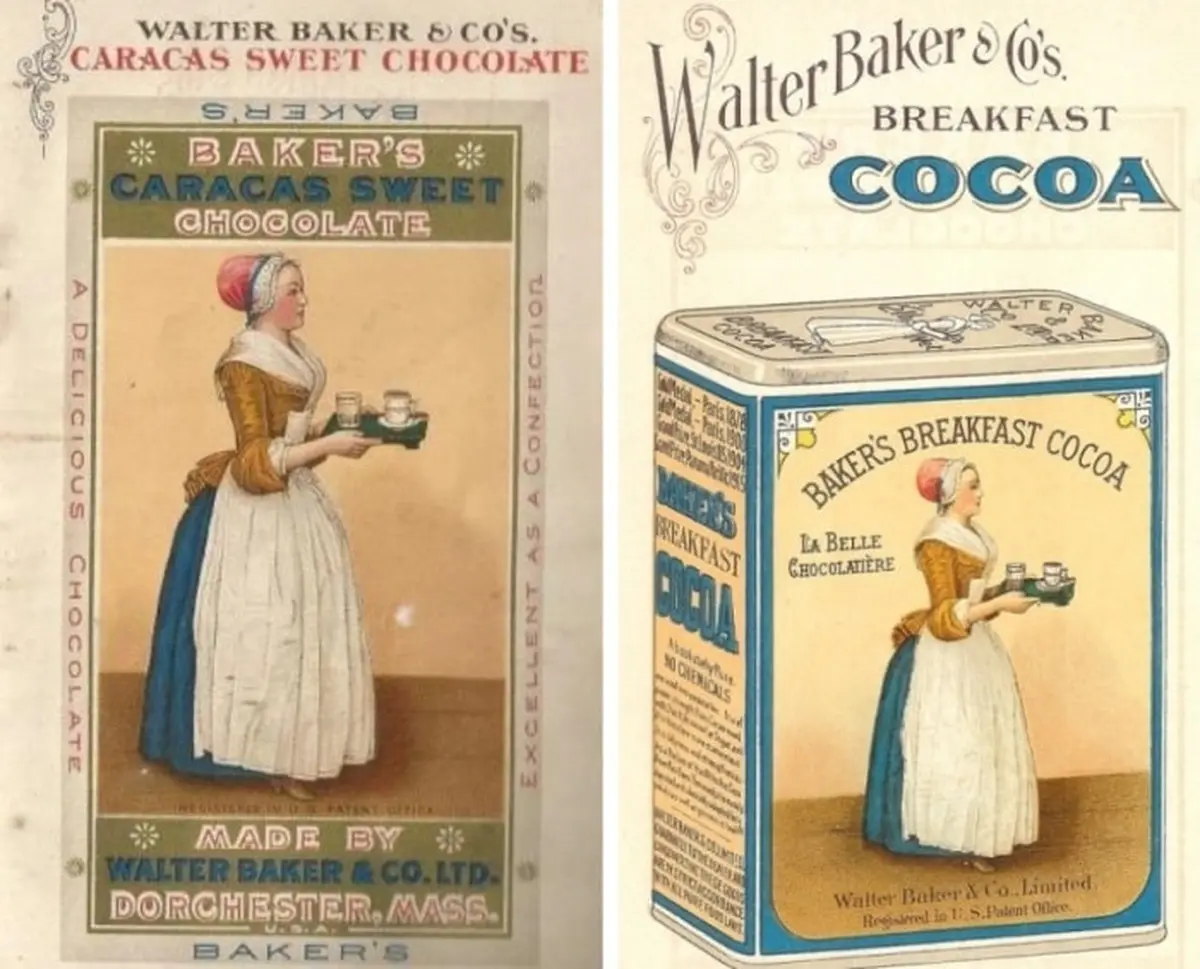

And now for the most interesting part. In 1862, Henry L. Pierce, president of the American chocolate company Walter Baker & Company, visited the Dresden Gallery. Upon seeing the “Chocolate Girl,” he realized: here it is, the perfect face for a brand.

The company acquired the rights to use the image, and it was a brilliant move. By the early 20th century, the image of the girl appeared on every package of , in every advertisement, on postcards, and recipe booklets.

It was Baker’s who popularized the romantic version of the Cinderella story – it fit perfectly into their marketing strategy. Tradition, elegance, true love – all of this was meant to be associated with the brand.

The “Chocolate Girl” became one of the first trademarks in U.S. history and one of the oldest in the world. The company used this image for over a century – and the girl from the portrait turned out to be the perfect ambassador. She never ages, never gets into scandals, never demands a raise, and always remains a paragon of modesty and refinement.

The Most Replicated Image

The fame of the painting “Chocolate Girl” has spread far beyond Dresden and advertising campaigns. Liotard’s canvas has become one of the most reproduced images in art history.

As early as 1843 – a hundred years after the painting was created – the Meissen porcelain factory released a porcelain figurine of the Chocolate Girl as a tribute to the artist for being the first to depict their porcelain in art. These figurines are still produced today, and antique examples from the early 20th century sell at auctions for 2000-6700 euros depending on size and condition.

Figurine of the Chocolate Girl, 19th century. Meissen porcelain

In the 1900s-1920s, special half-dolls inspired by the “Chocolate Girl” were produced in Bavaria and Thuringia – the so-called “tea dolls.” They were dressed in fabric and lace and used as decorations for needles, powder boxes, and teapot warmers. Today, these antique dolls are worth 1500-2000 euros.

Half-doll

The image was reproduced on postcards, posters, and reproductions. Today, reproductions of the “Chocolate Girl” can be purchased in many countries around the world, and some coffee shop chains use this image as their logo.

The Chocolate Girl never made it to the table. She remains frozen on the threshold, in the light from the window, with a cup in her hands. And perhaps that’s the best thing that could have happened to her. Because afterward, there would have been an empty cup, a wiped table, and no one would remember her face.