It turns out that this period was far more dynamic than scientists once believed. At the very least, it paved the way for the emergence of complex life forms like humans.

It turns out that this period was far more dynamic than scientists once believed. At the very least, it paved the way for the emergence of complex life forms like humans.

The term “Boring Billion” was coined in the late 1990s by English paleontologist Martin Brasier to describe the slow geological and biological development of Earth between 1.8 and 0.8 billion years ago.

Thanks to Brasier, many of his colleagues considered this period to be the dullest in the planet’s history, convinced that nothing significant was happening with its climate, tectonic activity, or biological evolution. But it seems that’s not the case.

Recently, a team of scientists from the University of Sydney and the University of Adelaide (Australia) announced that this time frame was, in fact, anything but boring.

What Did the Researchers Report?

According to the scientists, during the “Boring Billion,” tectonic plate shifts played a central role in transforming Earth’s surface from a toxic, unbreathable environment into a world filled with oxygen-rich, life-sustaining oceans.

Thus, the “Boring Billion” set the stage for an era that led to the emergence of advanced intelligent life, as reported by Daily Mail. Professor Müller, the lead author of the study, stated that it was the “Boring Billion” that “helped shape Earth’s habitability for life.”

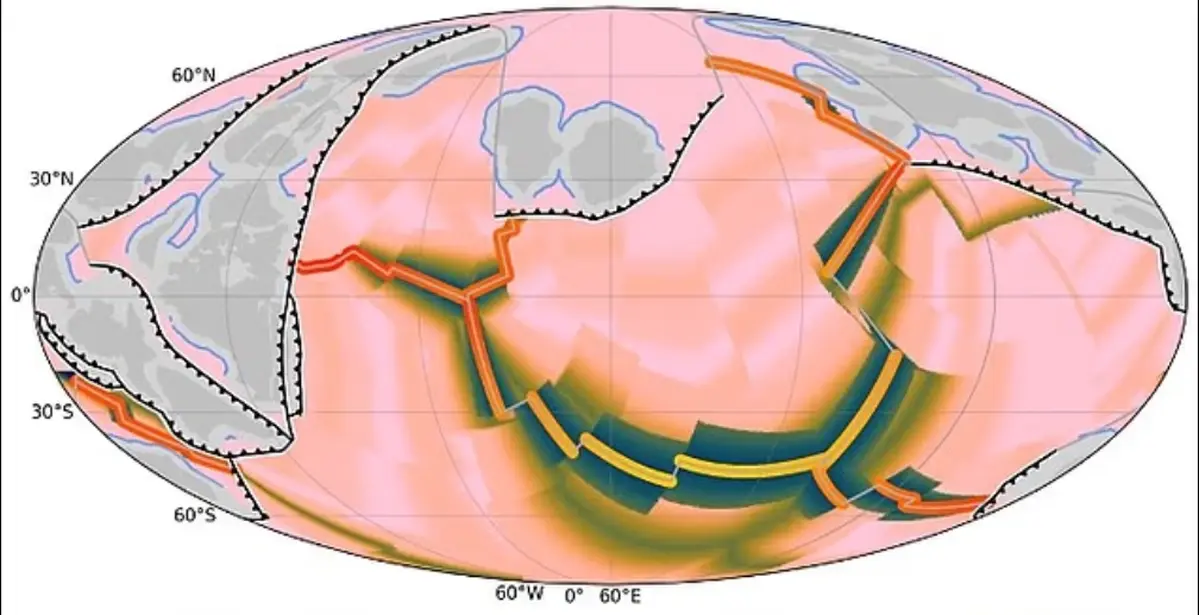

The team developed a computer model that illustrated Earth’s evolution from 1.8 billion years ago to the present day. The model reconstructed changes in plate boundaries, continental margins, and carbon exchange between the mantle, oceans, and atmosphere.

According to the researchers, at the beginning of the “Boring Billion,” our planet was home to an ancient supercontinent called Nuna. This landmass included parts of present-day Asia, Australia, and North America, as well as likely portions of West Africa and India. The breakup of Nuna initiated a chain of events that led to a reduction in volcanic carbon dioxide emissions and the expansion of shallow marine areas rich in oxygen.

Around 1.5 billion years ago, this fundamental change in atmospheric chemistry resulted in the emergence of the first eukaryotes. These are organisms whose cells contain a well-defined nucleus and other membrane-bound structures. The first eukaryotes were the ancestors of all complex life as we know it today, including plants, animals, and fungi.

The first primitive eukaryotes, which thrived in shallow marine zones, were pioneers in the sense that they were aerobic, meaning they required oxygen for growth and survival. The seas containing these zones were likely vast and oxygen-rich, providing a stable environment for complex life to flourish, the scientists noted.

Moving tectonic plates changed Earth’s surface environment.

About 900 million years ago, a new supercontinent, Rodinia, formed, encompassing nearly all of Earth’s landmasses. This continent broke apart roughly 750 million years ago, coinciding with the end of the “Boring Billion.”

Oxygen levels during the “Boring Billion” were significantly lower than they are today. It wasn’t until around 450 million years ago, when plants took root on land, that oxygen levels surged dramatically.

As for tectonic plates, it was only in the last few hundred million years that something resembling modern Earth took shape.

Recently, scientists have increasingly acknowledged the significance of the “Boring Billion.” Researchers at the University of Oxford referred to it as a “geological waiting room for the modern era of the Phanerozoic, leading to the emergence of intelligent life on Earth.”

A study conducted in 2017 revealed that photosynthesis began in plants about 1.25 billion years ago. This era may have laid the groundwork for the proliferation of more complex life forms, culminating in the so-called Cambrian Explosion 541 million years ago, marked by the emergence of new types of – possibly due to a sharp increase in atmospheric oxygen levels.

A new Australian study published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters showed that the “Boring Billion” was significantly more dynamic than previously thought.

Photo: Unsplash