The bright dream of every pedestrian.

“There will be neither books, nor newspapers, nor theater, nor cinema – there will only be television,” do you remember how the hero of a well-known Soviet film shared his vision of the future with barely restrained optimism? It somewhat turned out that way: over time, television took over people’s minds, but hardly anyone could have imagined the scale and consequences this could lead to. And then the internet appeared.

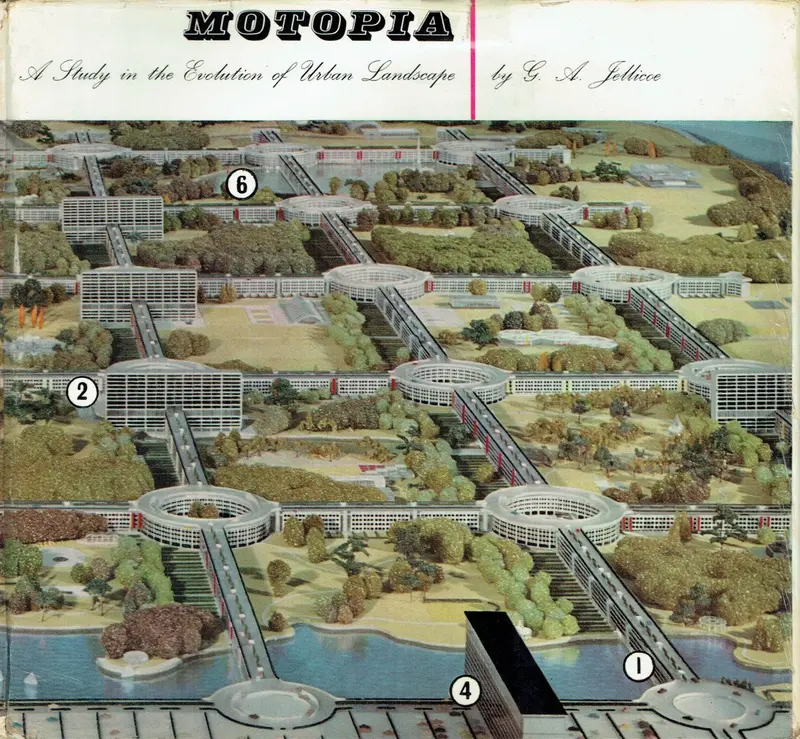

“No foot of any person will step where cars will drive. And no car will encroach on the area designated specifically for pedestrians,” said British architect, landscape designer, and somewhat of a futurist in urban planning, Jeffrey Alan Jellico, confidently sharing his plans with an Associated Press correspondent in 1960, around the same time as the Soviet “romantic of television.” Just imagine this picture: a city where cars do not roam, its residents move freely and calmly wherever they please, without worrying about traffic lights, jams, or traffic controllers at intersections. A true paradise for pedestrians. Although, no, cars are planned in this city, but… on the roofs of your houses. By the way, the city will be called Motopia. Well, did you have a laugh at that name in your twenty-first century? But such an idea was taken quite seriously by the British government.

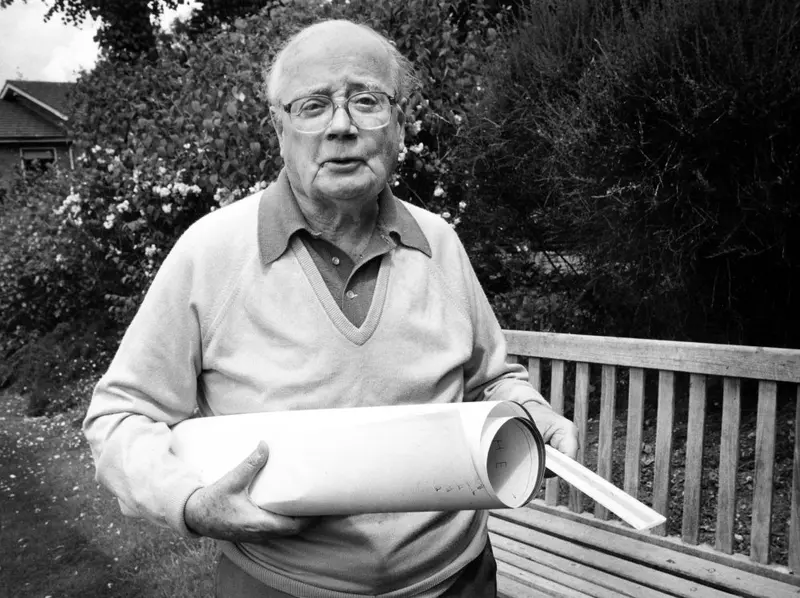

But first, it is necessary to talk about the author of this bold idea, in which he desperately believed and tirelessly advocated. At that time, Jellicoe, a contemporary of the century, was already 58 years old; he was a respected and renowned architect with a clear inclination towards landscape design. In the mid-1950s, he created a rooftop garden at the Harvey’s shopping center in the town of Guildford.

At the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire, a branch of the famous Rutherford scientific laboratory that focused on atomic fission research, he created the unique artificial hills “Zeus and Themis.” In the same Oxfordshire, there is another work by Jellicoe – the Ditchley House estate park, known for its famous guests, including monarchs, members of the royal family, and Sir himself. Winston Churchill The Oscar-winning film “The Young Victoria,” released in 2008, was filmed there.

In Runnymede, located in the English county of Surrey along the River Thames, the authorities have allocated about a quarter of a hectare of land for the creation of a memorial to the late John Kennedy. Jellicoe himself referred to his monument as “allegorical”: a stone-paved path leads to the memorial through a dense forest area.

Or here is the “Shute House” – a water garden, an original musical cascade in Shefford, which he worked on for 23 years.

Shute House

But what is this “Motopia” that is most associated with the architect’s name, why did it create such a stir in the early 1960s, and why are Jellicoe’s ideas still referenced decades later and applied to today’s context?

Don’t forget to look up from time to time.

In 1946, the New Towns Act was passed in the United Kingdom, granting the government the authority to quickly allocate land for new developments. Even before the end of World War II, the British began planning how they would rebuild London, with the key idea being to relocate residents to less populated suburbs and towns outside the metropolis. The rapid construction of such towns was primarily aimed at addressing the issue of overcrowding: in the first four years after the law was enacted, fourteen were built. Aesthetically, the newly created towns resembled each other and did not particularly impress leading architects of the time with their progressive ideas. By the 1950s, interest in this concept had cooled somewhat, but it returned closer to the 1960s when the “baby boom” began in Britain.

Motopia Jellicoe (let’s not lose the automatic associations with the word “utopia” in this name) was supposed to receive the status of an experimental settlement and be located 17 kilometers west of London, with a projected population of around 30,000 residents. The idea was for all of them to live in symmetrically constructed buildings, on the roofs of which it was planned to build… highways. And there’s the answer to the question of where cars fit into this story. Pedestrians separately, cars (even if on the roofs of your houses) – separately. On an area of 400 hectares, it was planned to build all the necessary urban infrastructure: shops, restaurants, schools, churches, theaters. The cost of the project was about 170 million US dollars (which at the time was considered hardly economically viable), and at the current exchange rate, that’s almost eight times more expensive.

The plan was to implement the principle of separating biology from mechanics: all transportation would move along special tracks that would be suspended just above the heads of pedestrians, and these tracks would be able to move and connect with each other in various combinations. Pedestrians, accordingly, would take their rightful place on the sidewalks. They could stroll safely and as relaxed as possible, but they would need to remember to look up periodically: the risk of a car flying down at high speeds from above would significantly increase. It was like something out of Luc Besson’s “The Fifth Element.”

In the same interview with the Associated Press, Sir Geoffrey optimistically stated, “Motopia is not only possible, it is practical because it is economical. Housing there will not be more expensive than apartments in high-rise buildings, such as the London municipality building.” Another appealing aspect of the British architect’s project is a city without heavy industry, no factories or plants. It was meant to be a so-called “dormitory community”: its residents would primarily earn a living through intellectual work or in the service sector.

“At the crossroads, there should be a roundabout, but no traffic lights,” Jellico told the BBC correspondent, “inside the circle we created what we call a ‘neighborhood circle’: a mini-center for the local population with clubs, pubs, a market, shops, newsstands, in other words – a favorite meeting place.”

“Let’s say I live somewhere on the outskirts of this city and want to get to another part of it,” the correspondent persisted, “what’s the best way for me to do that?” “I really hope you’ll leave your car and become a pedestrian,” the ‘father’ of Motopia replied calmly, “if the weather permits, you can take a walk through the very attractive scenery that consists of all the necessary components of a modern city, and if it rains, you can do the same under cover, through the arcades that connect the city to the center.”

Jeffrey Allan Jellico

Motopia remained a utopia.

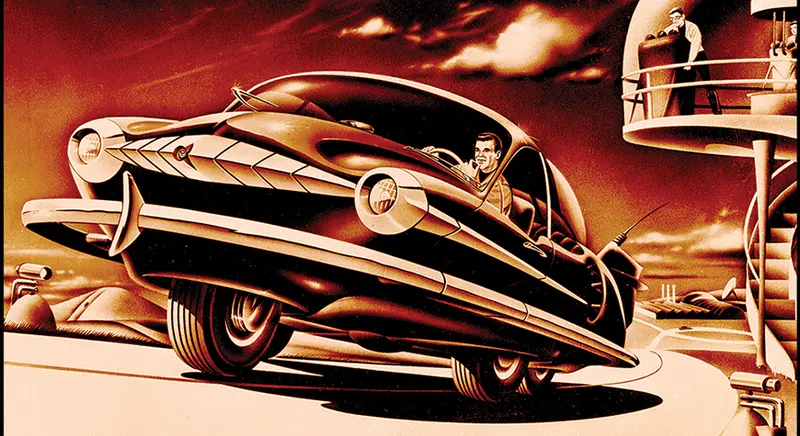

Here is another notable name from that time, also partially connected to Motopia: Arthur Radebo – an American artist, designer, and futurist. However, he is best remembered in the public consciousness as the creator of witty and popular comics.

Researchers of that era even claim that no one shaped Americans’ expectations about their future quite like Radebo, and the influential American popular science publication Wired referred to him as the “Da Vinci of retrofuturism.” From 1958 to 1962, he published a weekly Sunday comic strip titled Closer Than We Think, and this definition, which became the title of the publication, of course, referred to the future.

In his weekly comics, he illustrated the future in the most accessible form for everyone, unlike all scientific concepts and verbal descriptions of future visions. In the distant near future, Radebo’s mail carriers had jet packs, school desks were equipped with button-controlled automation, and carts autonomously traveled to stores for groceries and delivered them to citizens.

On September 25, 1960, the latest Sunday comic “Closer Than We Think” was released, dedicated to Motopia – the city of the future. However, the American artist made some adjustments to the plans of the British architect: the cars of the future in his drawings were not teardrop-shaped and barely noticeable, as Jellicoe had envisioned in his designs, but were more reminiscent of mid-twentieth-century Detroit cars, which is not surprising since the artist was from Detroit. The moving sidewalk in the drawings was depicted more clearly and vividly. Thus, across the ocean, people learned that significant changes were on the horizon on another continent.

From 1961 to 1970, the approach to the development of new cities in Great Britain became more creative, ambitious, and innovative, in line with the spirit of the times. Projects featured private cars, monorails, and even hovercraft transportation. However, the Motopia, with its pedestrian paradise, was never realized. It remained a pleasant memory and an ambitious plan from the mid-20th century. Similar ideas were proposed by Sir Jellicoe’s futurists: American architect Harvey Corbett, who was an advocate for cars and planned spaces for them in New York skyscrapers; another American, Richard Fuller, who created a project for a floating city; British visionary Ron Herron, who imagined a walking city (imagine falling asleep in your Kyiv apartment one evening and waking up in Budapest the next morning); and the flying city envisioned by Georgiy Krutikov.

In fact, Jellicoe envisioned the deindustrialization of major cities in the US and Europe in his bold plans, which began in the 1970s. A certain echo of Motopia reached the city authorities of Paris in 2017, when among activists and landscape designers, the idea increasingly emerged that the banks of the Seine should once again become a traditional place for walks and entertainment. The possibility of extending transport highways beneath the riverbed, featuring shops, garages, exhibitions, libraries, and more, was also considered. Sir Geoffrey Alan Jellicoe, a centenarian, passed away just shy of the new millennium at the age of 95, having witnessed what that very future looks like. Last year, the “Motopia? Past Future Visions” exhibition opened at the National Motor Museum in London, where, among retro cars that were supposed to traverse the rooftop tracks of this unique city, they also remembered the one who conceived it all.