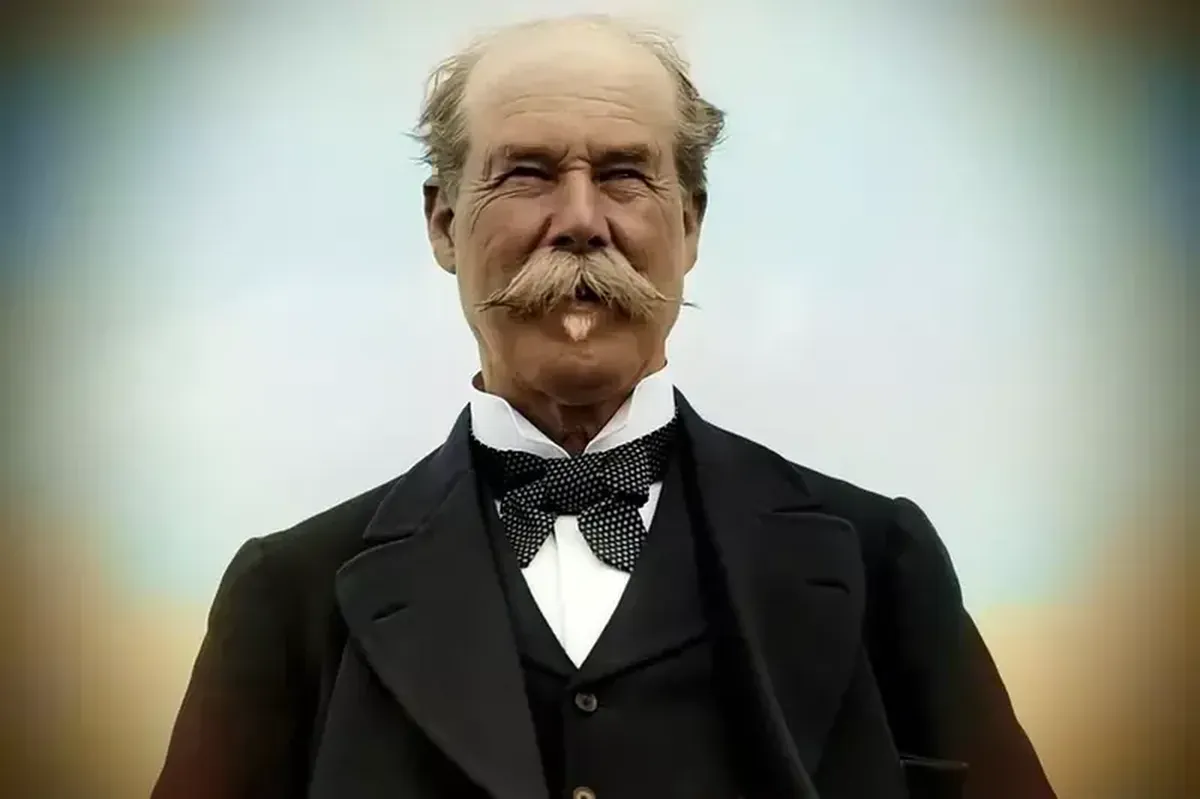

A creative businessman who introduced innovative approaches to the art of commerce built his renowned tea empire while already being a well-known millionaire. Hailing from the impoverished neighborhood of Glasgow, he amassed an immense fortune, royal attention, and public acclaim through entrepreneurial success, personal charisma, and a zest for life filled with inspiration, risk, and dreams.

Life Lessons

The journey to success for the creator of Lipton tea began in his childhood in the poor district of Gorbals in Glasgow, where Thomas Lipton was born on May 10, 1848, to Irish immigrants from Ulster. The Scot who would make Ceylon tea a staple of English life learned the trade from the age of five, helping his father in his grocery store. By the age of ten, Tommy Lipton was loading goods from ships onto carts and delivering them from the port to his father’s shop. After the death of his brother and sister, the boy was forced to leave school. At 15, he took a job as a cabin boy on a steamboat, and a year later, he found himself in the United States, where he worked on rice and tobacco plantations in Virginia and South Carolina.

However, the most significant education for this aspiring entrepreneur came from his subsequent employment at a massive marble palace of a supermarket on Broadway. Working as a grocery clerk in this “temple of consumerism,” he gained insight into the inner workings of a leading department store. The owner of AT Stewart & Co., one of the largest stores in the world at the time, was Alexander Turney Stewart, an Irish-Scottish immigrant (like Thomas Lipton). His innovative approach involved a fixed pricing strategy and low markups, relying on high sales volume. Thomas Lipton would later adopt this borrowed know-how in his own business.

Affordable Luxury

Five years in America gave the young Scot an understanding of how to build his own business back home. After returning to Glasgow in 1871, the 23-year-old entrepreneur opened his first grocery store, spending the £100 he had earned overseas, which marked the beginning of his journey to millions. At Lipton’s Market on Stobcross, the young merchant was both supplier and seller, as well as manager. He offered local residents a new shopping experience, selling not just groceries but also the feeling of “affordable luxury.” People were eager to part with their money in a pleasant place with bright lighting, sparkling cleanliness, and the white aprons of the staff. Customers were drawn in by elegant displays, reasonable prices, and impressive promotions that could sell tickets.

The success of his business was aided by original promotions: the inventive Lipton advertised his stores with giant cheeses and “pig parades.” In 1881, he famously ordered the largest cheese in the world from America for Christmas: the circumference of the cheese reached four meters, and its thickness exceeded 60 centimeters. A crowd of shoppers accompanied the unusual cargo from the port of Glasgow to the shop on High Street. When it became clear that the delivered product could not fit through the doors, hundreds of passersby followed the grocery giant to another of the entrepreneur’s stores on Jamaica Street, where the cheese wheel, made from the milk of 800 cows, became a centerpiece and a marvel in what was almost a museum display.

The Art of Selling

For two weeks, the public gathered around the extraordinary product, but that was just the beginning of a remarkable advertising campaign. It turned out that Thomas Lipton had hidden numerous gold sovereign coins inside the giant cheese wheel. When the “wizard” in white began slicing the “cheese with a surprise” the day before the holiday, long lines formed outside the display, hoping to win a Christmas gift, and the police had to maintain order in the store for several hours. After that “one-man show,” the giant cheeses in the windows of Lipton’s Market became heralds of Christmas in Great Britain. In Nottingham, they even rented an elephant to transport the giant cheese to the store.

After “conquering” Scotland, Lipton’s chain of stores expanded across the country by the mid-1880s. New locations of the recognizable brand always opened with great fanfare, preceded by mysterious announcements about the approach of some grand event. Butter sculptures in store windows and the pig parade that caused a commotion in the city center were examples of Lipton’s unforgettable tricks that drew attention to the openings of his new stores. These theatrical spectacles were the facade of a business plan aimed at expanding the network and increasing profits. The main innovation in this direction was the elimination of middlemen in purchasing and a shift to direct supplies from producers.

Onward with Music

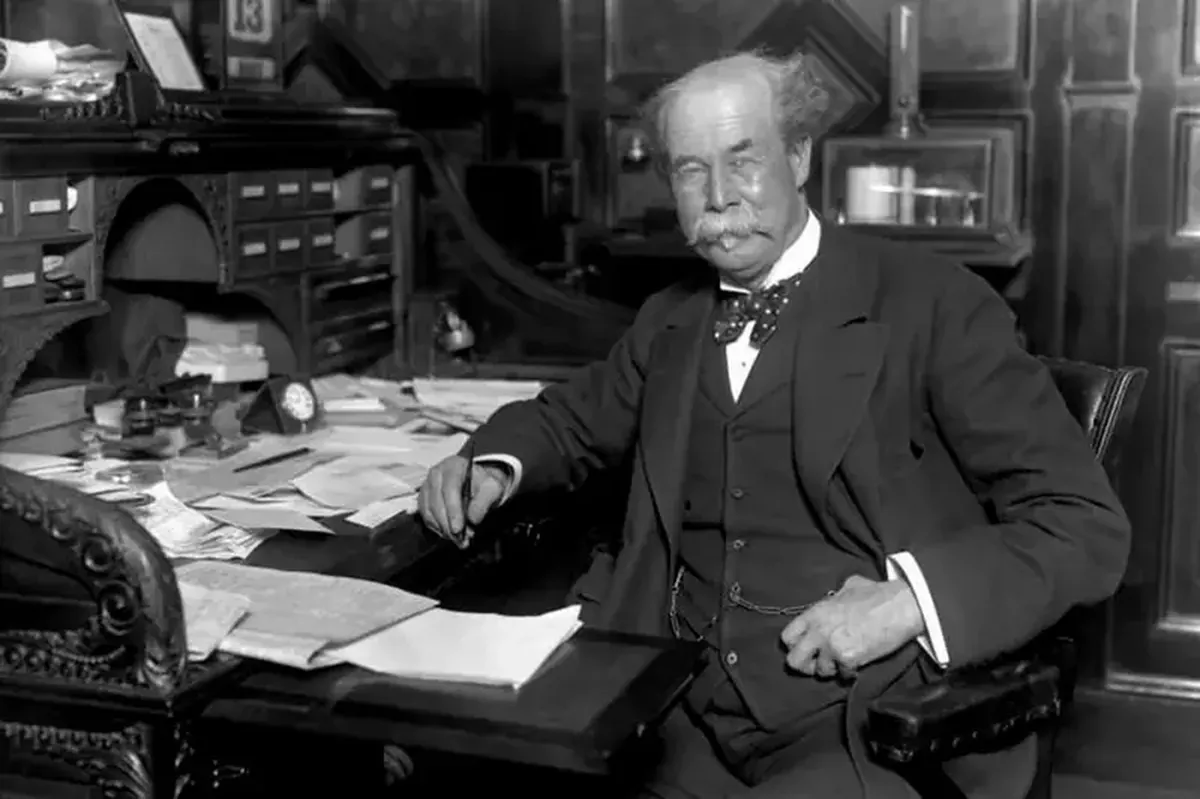

Lipton first employed a new supply model back when he had to pawn his gold watch to pay Irish farmers. But later, he managed to buy back most of the supplier companies and close the production, packaging, and distribution cycle within his own business empire. The next step for the entrepreneur in expanding his business was the “conquest” of America. There, he also eliminated middlemen by purchasing a meatpacking plant and naming it after his mother. In addition to the meatpacking plant in Chicago and British pork processing businesses, Thomas Lipton acquired tea, coffee, and cocoa plantations in Ceylon.

In search of new business opportunities, Thomas Lipton turned his attention to the industry that has become synonymous with his identity: when the number of stores in his chain exceeded three hundred, the 40-year-old millionaire became interested in tea. After buying his first tea plantation in Sri Lanka in 1890, the newcomer to the tea business quickly outpaced his competitors. Lipton tea became competitive because there were no unnecessary links in the “from plantation to teapot” chain: the tea magnate had his own trading, production, and logistics bases (he even had his own fleet). The arrival of the first shipment from the Ceylon plantation to Lipton’s store was celebrated with a parade of bagpipers and an orchestra.

The English Way of Life

On the five tea plantations he purchased in Ceylon, Thomas Lipton conducted experiments to achieve high quality at low prices. By the time Lipton entered the tea business, the blends in a London shop on Minchin Lane were mixed in various combinations, and their quality could not be guaranteed. The new tea baron standardized the blend, ensuring that Lipton tea (both green and black) maintained consistent freshness and flavor. The Lipton brand was the first to package tea and use attractive bright yellow packaging. Lipton sold tea not in boxes like others, but in small packets weighing half a pound and a quarter pound. While previously a drink for the wealthy cost 50 cents per pound, Lipton’s tea could be purchased from the producer for 30 cents.

This price for a once-valuable commodity, which had cost more than gold until the mid-19th century, no longer deterred buyers and was accessible not only to the Victorian middle class but even to ordinary workers. At the same time, Queen Victoria herself was a fervent admirer of Lipton tea. Upon entering the upper echelons of Victorian society, Lipton donated £25,000 (over £2 million today) to a charity banquet in honor of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. That same year, for his contributions to shaping the English way of life, the businessman was knighted. According to eyewitnesses, the ease with which the grocery magnate conducted business, his sense of humor, and his charm made him a celebrity among the upper class.

The “People’s Star”

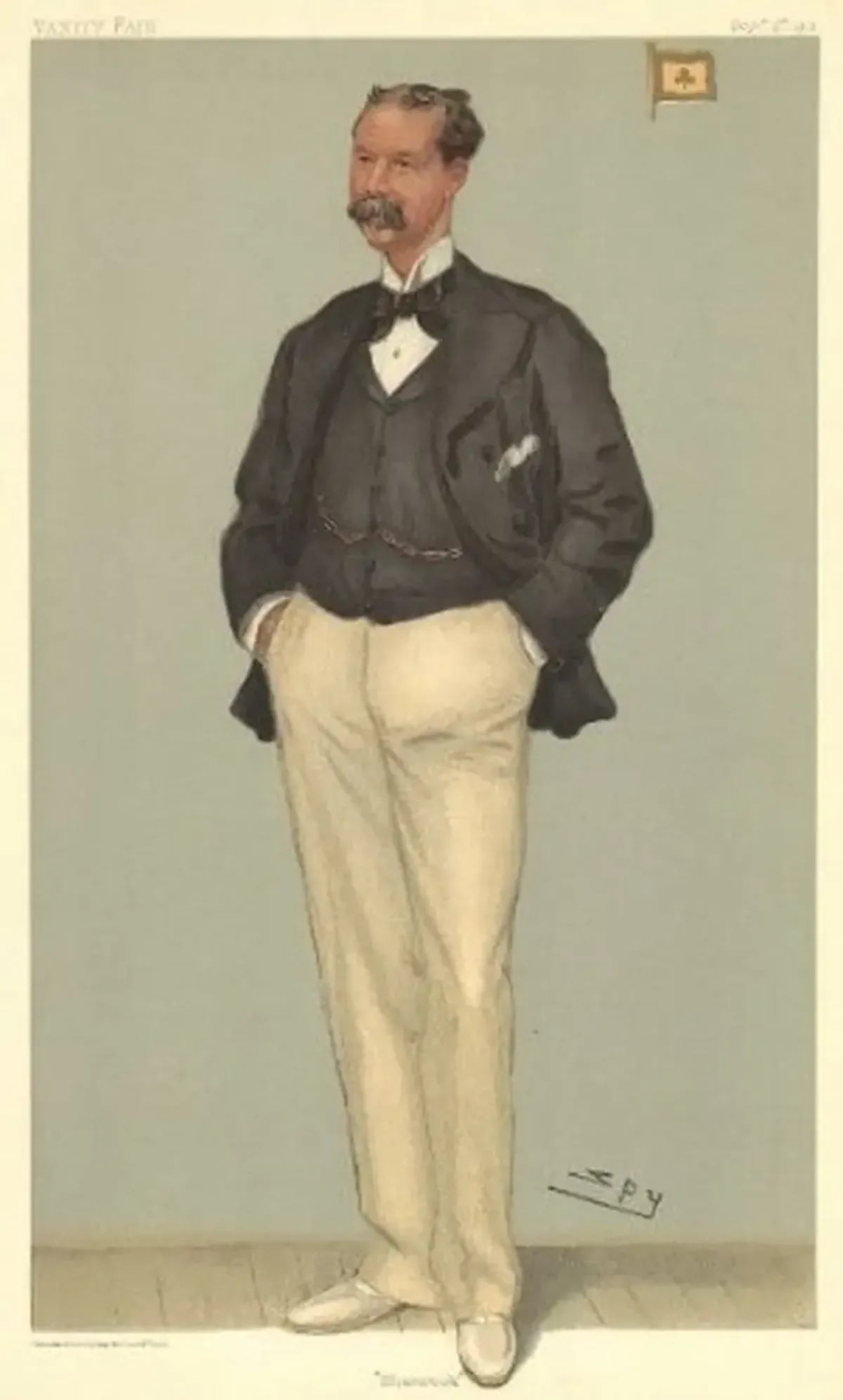

In 1898, the capital of this member of the Masonic Lodge Lodge Scotia No. 178 in Glasgow was estimated at £120 million (now about $1 billion). At that time, the founder and owner of Lipton placed shares on the stock exchange, retaining control of the majority. After his 50th anniversary, Thomas Lipton embarked on another important venture, realizing that it was time to fulfill a childhood dream. Once, while watching ships in the port of Glasgow, the young dreamer Tommy crafted models of the vessels he saw and launched them into the city’s waterways. Now, Sir Lipton could afford to join the world of elite yachting and compete for the highest prize in the oldest regatta – the America’s Cup. A professional yachtsman was his most steadfast rival in history.

A member of the Royal Ulster Yacht Club, based in County Down, Northern Ireland, in Bangor, touched the hearts of the Irish even in his first competition in 1899, which he lost. His yacht Shamrock (named after the plant that symbolizes Ireland) garnered support during the races from both locals and foreigners, and he made new friends, while the Lipton brand became even more popular when images of Lipton the yachtsman appeared on tea packaging. Fans clamored to take photos with the brand owner and get his autograph. The popularity of Thomas Lipton can be compared to that of Steve Jobs or Elon Musk. He was an example of a “popular millionaire,” whom many considered a “people’s star.”

The Cup of Love

Guests aboard Lipton’s luxurious yacht Erin included U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, German Emperor Wilhelm II, and inventors Thomas Edison and Guglielmo Marconi. Eyewitnesses reported that Thomas Lipton forbade discussions of politics or religion on board, and no one ever broke that rule. When World War I interrupted the yachtsman’s participation in the 1914 competition, he converted his yacht Erin into a floating hospital and donated it to the Red Cross. However, the following year, the vessel was sunk by a German submarine. “If I could save people, I would give everything I had for it,” the shocked Sir Lipton said at the time. Instead, he was unconcerned about the elusive America’s Cup.

Having come close to sporting victory in 1920, the millionaire once again ended up empty-handed, humorously referring to the coveted trophy as “an old mug slipping through my fingers.” Lipton’s humor and his unwavering determination to achieve his goals evoked both sympathy and admiration from the public. After the Scotsman’s fifth unsuccessful attempt to win the “cup of dreams” in 1930, the Mayor of New York presented the “cheerful loser” with an award for perseverance and sporting spirit – the golden “Cup of Love,” purchased with donations from Americans. The beloved wealthy man passed away on October 2, 1931, leaving most of his multi-million fortune to his hometown. Despite the change in ownership of the brand (now Unilever), the name of its illustrious creator continues to live on in the name of the unparalleled Lipton tea.