The “cosmic” projects of the “destroyer of geometric laws” resemble mysterious objects from extraterrestrial civilizations—her revolutionary construction style has made a significant impact on the world. The professional journey and creative achievements of the first Arab woman awarded the Pritzker Prize (the “Nobel Prize” of architecture) reflect the meaning of her name: Zaha, which translates from Arabic as pride.

The Monumental Mesopotamian

The influential publication The Guardian described the Iraqi-born British architect as a “liberator of geometry.” However, it might not be appropriate to apply feminine forms to such an extraordinary personality—she likely would not have appreciated them. Zaha Hadid’s entire biography speaks to her uniqueness. A representative of a culture that does not embrace female independence or autonomy, she not only broke free from the chains of tradition but also pushed architecture beyond stereotypes. Starting with a fascination for Constructivism and a fan of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square,” she became the most prominent figure in Deconstructivism.

Beijing Daxing International Airport

Dubbed the “Queen of Distorted Perspective” by the press, she was an advocate for warped planes, curved or broken lines, and sharp angles, confidently liberating space and giving it complete freedom and new expressiveness. This inspired Mesopotamian had the character to withstand criticism, defend her innovation, carve a path in a male-dominated field, and establish herself as a leading figure in architecture at the turn of the 21st century. In the U.S., Zaha Hadid became a foreign member of the American Philosophical Society, and in London, she was the first woman to receive the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Gold Medal and was named a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. Interestingly, she found the title of Dame somewhat unsettling, believing that in her work and life, “there’s nothing feminine except for the skirt.”

“I can’t even cook,” Zaha Hadid confessed, noting that her London home lacked a kitchen: the spartan style of her old residence on Courtfeld Gardens did not include such a space. Instead of a kitchen counter in the room where a hearth might have been, there was a massive drafting table where she worked. She lived near her office, rarely at home, drove a reliable BMW for work, and met friends at London restaurants. Zaha Hadid’s personal life was dedicated to her life’s work: architectural and engineering design took precedence over starting a family. She was never married and had no children. The architect stated that Zaha Hadid’s children were her completed projects, and her family was her architectural firm.

How to Become an Architect

The future superstar of architecture was born on October 31, 1950, in Baghdad, to Muhammad al-Hajj Hussein Hadid, a co-founder of the National Democratic Party, and artist Wajihah al-Sabunji. The famous models and daughters of construction magnate Mohamed Hadid—Gigi and Bella Hadid—are not her relatives; Zaha Hadid had older brothers, Haytham and Fulat (the latter was a scientist). Their children ultimately inherited Zaha Hadid’s immense future wealth: £67 million will be distributed between a trust company managing her international business and several nieces and nephews, one of whom, Rana, will also become an architect.

Zaha Hadid made her professional choice after a childhood visit to ancient Sumerian ruins—this was her first impression of extraordinary architecture. The desire to design buildings unlike any other was also inspired by magazine photos of the works of Frank Lloyd Wright, the creator of “prairie houses,” that she saw as a child. The daughter of an artist was captivated by the open plans of the American architect, who created masterpieces of “organic architecture.” After asking her mother and father what the people who design such things are called, the fascinated girl expressed her desire to become one of them. In her childhood plans, she also considered becoming a fashion designer or an astronaut, interests she somewhat realized as well.

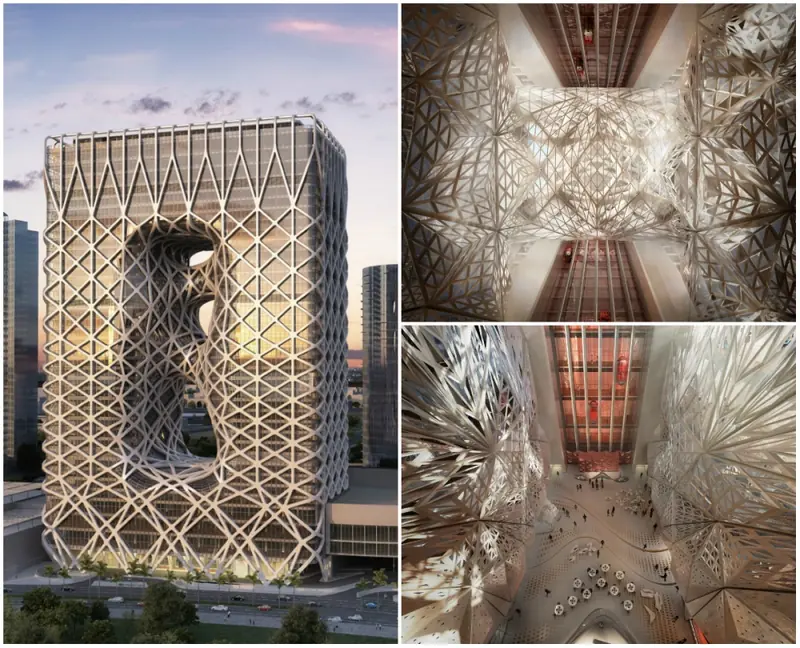

40-story hotel. Macau, China

Futuristic design and complex engineering solutions became Zaha Hadid’s signature style, as she was unafraid of bold fantasies or integral calculations. While she had a natural talent for drawing, she had to study mathematics (which she learned at the American University of Beirut). The support of her successful entrepreneur father, a graduate of the London School of Economics (after the monarchy was overthrown in 1958, the left-liberal politician even served as Minister of Finance), ensured her education at prestigious institutions in her chosen field. Leaving Iraq in 1968, Zaha Hadid would not return to her homeland for another 40 years. After studying mathematics at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, she moved to London to attend the Architectural Association School of Architecture.

The Inventor of 89 Degrees

Zaha Hadid’s instructor was Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas—the theorist of Deconstructivism defined the creative style of his most talented student, who would surpass her teacher. For each of her projects, Zaha created several artistic sketches that featured no right angles (due to this freedom, she was dubbed the “inventor of 89 degrees”). She fragmented buildings into pieces, astonishing her mentors with associations to shattered ice blocks, mountain cliffs, tectonic shifts, and solidified lava flows. “Her projects are the least like the result of human activity,” Koolhaas remarked about Hadid (he immediately recognized her unique potential and invited her to work in his office). “This is a unique phenomenon, a planet moving in its own orbit.”

Guangzhou Opera House

Recalling her student days, Zaha spoke of her fascination with Kazimir Malevich’s avant-garde. This is even reflected in the title of her thesis, “Malevich’s Tectonics”: in the design of a populated bridge over the Thames, she painted using the method of projection. The high-rise hotel on London’s Hungerford Bridge was turned “upside down” by the student. Later, she would turn both a skyscraper and an unusual club on a mountain peak “upside down.” By breaking the rules, Zaha Hadid built her creative foundation on the movement and deformation of architectural stamps. By giving dynamic impulse to glass and concrete, she convinced more and more people that rectangular shapes are not the only way to organize space.

Fire Station

Understanding her logic did not come easily: the innovator, who founded her own architectural firm, Zaha Hadid Architects, in 1980, had to spend 10-15 years dealing with routine tasks. Hundreds of lost tenders and survival on small orders could have made anyone give up their ambitions, but not this maximalist. She persisted, continually proposing bold ideas that clients were not yet ready for. The breakthrough came with the design of a fire station shaped like a stealth bomber for the Swiss furniture company Vitra. Following that would be contemporary art centers in Cincinnati, Ohio, Rome, and an office building for the new BMW AG factory in Leipzig (the revolution in workspace organization in the “best building of the year” was the placement of the car conveyor above the administration, rather than the other way around).

BMW AG Factory Building in Leipzig

Museums Yes, Prisons No

Zaha Hadid’s most significant structures include the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku (Azerbaijan), which received the award for best design of the year from the British Design Museum; the Sheikh Zayed Bridge in Abu Dhabi (UAE); the Guangzhou Opera House; the Innovation Tower at the Jockey Club in Hong Kong Polytechnic University; and the Galaxy SOHO complex in Beijing (China); the London Aquatics Centre and the Riverside Museum in Glasgow (UK); the Library and Learning Center at the Vienna University of Economics and Business (Austria); the Port Authority Building in Antwerp (Belgium); the University of Michigan Museum of Art in the U.S.; and more. By embodying her creative imagination in new forms, Hadid studied the structure of living organisms, wave movement, and melting ice. Zaha drew inspiration from natural forms—her buildings reflect mountain ridges and dunes, clouds or leaves, droplets and streams. She refused to build prisons, no matter how attractive the offered sum was.

Galaxy SOHO Urban Complex. Beijing.

In addition to grand architectural forms, Zaha Hadid created exhibition installations, stage sets, paintings, furniture, interiors, jewelry, custom accessories, artistic items, and designer footwear. Zaha Hadid designed art objects for the French fashion house Louis Vuitton and the jewelry company Swarovski, collaborating with brands like Georg Jensen, United Nude, Stuart Weitzman, Lacoste, Nicholas Kirkwood, Niel Barrett, and others. By the first decade of the 21st century, Zaha Hadid’s intimate works had made their way to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt. Her lectures and master classes attracted audiences worldwide, and her London office expanded into all neighboring spaces, adding several hundred hired employees, with tasks planned out for the next ten years.

Zaha Hadid’s design lamp for Sawaya & Moroni

“My architecture has no nationality, just as there is no longer a country where I was born,” noted the architect of Western education with Muslim roots. Zaha Hadid watched with pain as events unfolded in her war-torn homeland. She empathized deeply with Iraq, where military conflict raged from 2003 to 2011. “The Iraqis did not deserve the horror they found themselves in,” Zaha said. “The country, divided into parts, lies in ruins. The war has brought much sorrow, but the embargo is the worst disaster. We need to start building something there to instill hope in people.” This was Hadid’s response to the British press’s question about why she accepted the invitation to design a new building for the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI).

Signature Towers. Dubai, UAE

A British Farewell

The last project of Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid—a 170-meter skyscraper on the banks of the Tigris—will become the tallest building in Baghdad. This year, the construction of the CBI headquarters is set to be completed without the author’s supervision: like many other ideas from the “queen of curved lines,” the grand structure is being brought to life by her colleagues at the firm. About 40 large-scale projects that Zaha Hadid did not manage to complete remain in development. The founder of Zaha Hadid Architects passed away on March 31, 2016—her life was cut short in the same city where, at the end of 2005, she was named Designer of the Year. At the age of 65, the global icon unexpectedly died of a heart attack in Miami, where she was being treated for bronchitis.

This death shocked the design world and made everyone realize the significance of such a loss. It turned out that Zaha Hadid’s works served as a catalyst for recognizing Deconstructivism as a cultural phenomenon linked to architecture, philosophy, and fashion. The projects of this outstanding architect evoke strong emotions in both supporters and detractors alike. Zaha Hadid’s structures allow contemporary society to glimpse into the future, which the architect materialized through her developed creative intuition. Her bionic masterpieces refresh and rejuvenate the appearance of cities with traditional architecture, making it easy to identify the author’s name.

As a creator of original recreational spaces and stylish complexes, she left humanity with examples of high architectural craftsmanship and aesthetic taste. One of her unique objects, featuring man-made valleys with hills and craters, has even been included in the list of the “seven wonders of the world.” When Hadid’s fame spread across the ocean, the architect proudly stated, “I have finally overcome all barriers in my professional journey, but it was a long struggle that made me tougher—women in architecture need more confidence.” When her name was associated with the “liberation of Arab women” and feminism, the master of new forms noted that she was not concerned with gender issues, “but if her example helps someone, she would be willing to be that.”